II. TEACHERS MUST MAINTAIN CONTACT WITH PASTORS IN THE FIELD

Ephesians 1:17-23 gives us insight into the divine process of theological education: God Himself gives His people (the members of the local church in Ephesus) a spirit of wisdom and revelation to know Him and His program. The teacher must help his student-worker to participate in this divine education process. What he studies should correspond to the activities of the local church where he works. Essential elements of doctrine, Bible and church history are introduced into his course where they best meet the needs of those people for whom he is responsible. We do not give doctrine and Bible a lower place in the obedience-oriented curriculum: they take on a surprisingly new importance when related directly to the life and activities of a growing congregation. This requires constant communication between the teacher and the churches – the nervous system of the pastoral course (Figure 3, page 6).

Experienced pastors and church planters in the field should inform the teachers what steps each student ought to take next. The student’s own reports also inform the teacher of his changing needs. The educator designs the broad course of study with its general objectives and unchangeable biblical goals. But he allows flexibility for dealing with the changing, immediate objects, as the student’s converts progress. In a new church the immediate objectives are more obvious: the congregation simply begins to do the things ordered by Christ, one by one. In an older church many needs normally arise; the student should not lack opportunity to apply different studies to them. Sooner or later he will need to apply the whole Word of God, important examples from church history, vital doctrines and pastoral work.

A seminary remaining independent from the churches can hardly have an obedience-oriented curriculum. The theological institution must place itself in a position of cooperation with the churches. Each local church should incubate pastors in collaboration with a resident or extension seminary. Christ gave the power to the Church – not to an autonomous seminary – to educate His people (Matt. 28:18-20). The seminary working within this sphere of authority finds the local church to be its most valuable classroom. Like a lens focusing sunlight on one sharp point, the Holy Spirit uses the church to integrate different elements of study into one program, just as He coordinates different ministries in one body (Eph.4:1-16).

Seminaries fear control by the churches, which in turn fear control by the seminaries. The seminary defends its independence in the name of academic freedom, scholarship and intellectual honesty. It may recognize the authority of Scripture but this is not the same as submitting to Christ’s authority given to the Church, through which God educates His own people theologically. We do not ask for the churches to control the seminary nor vice versa. The mutual suspicion is allayed only when both agree to share in the education process, appreciating the contribution of the other to its own ministry. The decisive factor is not the control but communication, to coordinate the student-worker’s service in a local church with his studies.

This two-way communication between pastor and educator is as vital as that between a military commander and his trainers. During a long campaign the troops are repeatedly briefed and oriented. As they pass from one objective to another they are re-equipped for their next encounter with rubber rafts, snow shoes, gas masks or anti-tank weapons, according to the intelligence reports and commander’s directive. The pastor student may not need to learn how to inflate a rubber raft; but he will need to know how to discipline a disorderly member of a new congregation. For this he needs special equipment. His teacher must know what his work is and relate the theoretical studies to it.

Such teaching is challenging; it spoils us for the conventional classroom. The student-worker also devours his studies with an eagerness seldom found in a traditional institution. He is obeying Christ! As part of a conquering army, he is responsible for his part of the work in some local church. A commanding general would not send his companies into battle under officers from an autonomous military academy which ignores his orders in the name of intellectual freedom! Would his trainers, set apart from the realities of a modern battlefield, make their own rules and design their own curriculum along traditional lines? Military trainers use constant information from the lines and directions from their commander. The Christian educator, like the strategist at the mapping tables, should interpret communications from the field, from spies behind the lines, and from the General Himself, in order to mobilize his troops for advance. In any crusade – military or missionary – those in action should report continuously from the field. Reports of progress and urgent needs clarify our immediate objectives as we work in obedience to our Supreme Commander’s general orders. Immediate educational objectives change from week to week, according to the progress and needs of those for whom the student-worker is responsible.

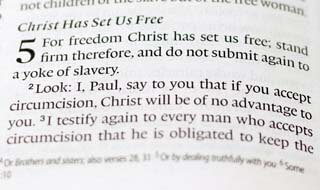

III. WE MUST TEACH DOCTRINE ALONG WITH ITS DUTY

The teacher must enable his student to fulfill the practical obligations of every doctrine. We do not tack on an “application” to it: rather, we approach doctrine out of a primary desire to obey Christ. Pastors should mobilize all the members of the congregation for service; Ephesians 4:11-16 indicates that pastors should equip the “saints” for the ministry. The Holy Spirit coordinates their different ministries.

Theological truth, properly taught, moves us to serve together as a body. But it cannot when we partition it into specific subjects and teach each one separately. We should relate different theological truths by focusing them on one specific church activity. Systematic Theology seeks to relate divine truths logically, but outside of their normal setting. The Spirit of God brings these truths into focus as He coordinates the different ministries within a growing church. He integrates different elements of Bible doctrine, history and Christian education, etc. as we apply them to men’s lives, struggles with the world, contradicting philosophies, politics and human relationships.

How can our student learn to harmonize apparently opposing interests in his congregation? An elder with the gift of teaching interests himself in the details of biblical doctrine. Another with the gift of prophecy is more concerned about the long range implications of theological truth for men in today’s world; he interprets church history, past present and future, to show us our position and duty before God. another with the gift of exhortation just wants to get the job done; he enjoys books on counseling, evangelistic methods and mission strategy. A deacon with the gift of serving wants better worship facilities; he reads books on ecclesiastical architecture and urges the music committee to buy new hymnals with more hymns of praise. Another volunteer works with a boys’ group and community projects; his wife plants flowers around the parking lot. The pastor cannot harmonize these different interests and abilities in the classroom nor from the pulpit. An experienced pastor governs with wisdom, unifying these men as they obey Christ together as a team. The student-worker observes and learns how God’s Spirit coordinates different people, interests and truths in the one combined ministry of the body of Christ. He discovers a cohesive factor in Spirit-motivated obedience to Christ. Figure 4 shows how different studies are related as they contribute to a certain activity ordered by Christ.

To relate doctrine and duty requires a “vertical” treatment of doctrine. We begin with God as the source of all truth and authority. His attributes find expression in the eternal decrees of God the Father. These decrees are wrought within creation by God the Son, whose work is applied to man by the Holy Spirit. Man responds in simple obedience. We start with God and end with man. The intermediate steps in this vertical application form the content of a doctrinal study. Any systematic study that fails to begin with God or end with man’s obedient response falls short of the biblical ideal. It will not really contribute to the activities performed by an obedient church. (See figure 5).

A “horizontal” approach to doctrine does not necessarily begin with God nor end with man’s duty. Like medieval scholasticism, it groups doctrinal truths in parallel or horizontal categories, comparing similar ideas. It fails to touch both heaven and earth. The prophets and Apostles show us how o teach: they presented theological truth which touched men’s daily life in a disturbingly practical manner. They never taught doctrine for its own sake.

A resident education program can hardly require every class to have its corresponding practical work. But special practical work classes can gear the student’s studies to his congregation’s growth. The teacher of this practical work class can help the other teachers make assignments helpful for each student’s need. See figure 6.

The teacher of the obedience-oriented pastoral course is responsible for his student’s weekly progress. He teaches the same general content as the traditional seminary or Bible Institute professor, but no in the same order. He gives his student what he needs for his own changing needs and he takes on more and more responsibility in his church.

How can we prepare textbooks which focus different areas of study on a given activity? First of all, we need to detach our list of educational objectives from any corresponding list of subjects and texts. If the two lists run parallel, each course or text can deal only with objectives in one specific field (Figure 7).

The subjects and textbooks in Figure 7 parallel the educational objectives with little interrelation between different areas of study. We can show their interrelation by plotting the lists on a two-axis graph and restating the subjects in terms of activities ordered by Christ (Figure 8).

We do not really need a graph except to visualize the integration. An accurate graph demands too many details, revisions and additions. We can integrate the studies easier by continuously filing objectives, needs and studies under their corresponding units. The file, with a folder for each congregational activity, can grow and grow without confusion. Each folder yields a textbook. It almost writes itself if we keep filing the significant information gleaned from students’ reports of congregational needs and adding the relevant theory as we think of it.

Resistance to such a practical study of theology always results. Teachers, especially those conditioned by the traditional academic disciples, cannot appreciate the flexibility required unless they have a dedicated pastor’s heart. The same applies to the students; the Honduras Extension Bible Institute does not normally enroll single young men. There is no arbitrary rule against it. They simply do not adjust to this practical application of doctrine. With some happy exceptions, most single young men care only to study or teach theory; they lack the maturity and respect of their community to do pastoral work. Some want to study primarily for material gain. The single young men are instructed but no in the extension class. One of the older extension students teaches them in a separate class.

Figures are in the original booklet which can be ordered from the author.

For help with materials or further information write:

CHURCH PLANTING INT’L

9521-A Business Center Drive

Cucamonga, California 91730-8002