CHAPTER 3: On ROMANS 7 From Law to Grace

OUR chapter this morning will be Romans 7. It is a specially difficult one. It is well know to have been the subject of age-long discussion and contention. We shall need the humble heart of a child as we study it. Let us pray that the Lord will deliver us from biased and prejudiced minds. If we are quite certain we know all about it, and no theory but our own can be right, we shall get nothing out of it. What I am going to say is simply what I see now to be the chapter’s meaning. There will be no dogmatism; I have no sense of finality in my heart, but an open mind to receive any corrections, if what I set forth is not according to the mind of God as expressed here in His Word.

First look at the structure of the chapter. Take the first three verses; they are impersonal. Then verses 4-6, where you have the first personal pronoun in the plural. From verse 7 to the end you have the pronoun in the singular, “I”. That might do to indicate the sections of the chapter, if we add that the last section is divided into two. The chief limiting verses are 4, 7 and 14. At each of them there is a new beginning. The first section (verses 1 to 3) seems to be speaking of our liberation from under the “law” by death. The second section (verses 4-6) shows the actual effect of the law upon the unregenerate heart. The third, from 14 to the end, the subject seems to be the dual nature of the believer and the inevitable conflict between them. It would seem as though Paul had announced the subject in chapter 6:14, where he says, “Ye are not under law”. How are we not? The answer is in Rom. 7: 1-3. Why are we not under the law? The answer is given from Rom. 7, verse 4 to the end. In the midst of that long passage there is a digression (verses 7 to 13) in which Paul vindicates the law, from a possible reflection upon it.

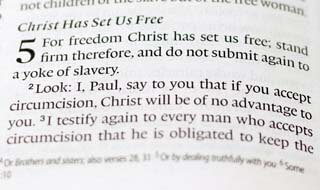

Why then are we not “under the law”? First, because of the law’s inability to produce holiness (verses 4,5,6). Secondly (verse 14 to the end, and into chapter 8), the reason why we are not under law is because a state of “no condemnation” is an essential condition of spiritual life and growth.

The chief contention over this chapter arises from the question whether this passage of spiritual autobiography describes the regenerate, or the unregenerate man. As a good principle, remember that it is not the habit of Scripture to give much time or space to unregenerate experience. It is difficult to see how such a thing could be helpful, especially such a long discussion as this. Whatever view be taken as to the meaning of this chapter, I cannot but feel that the culmination of the discussion is to be found in the first verse of chapter 8, “There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus”, and it is unfortunate that these words should have been divided from chapter 7. The argument seems to be followed in order to reach the conclusion expressed in this verse, that there is now, even at the present time, in spite of the conflict that goes on, in spite of the dualism in our being, there is now “no condemnation” to those who are in CHRIST! There is constant watchfulness needed on the part of the regenerate believer, for there are the irrepressible efforts of indwelling sin to express itself; but in spite of all, there is the existence of a “new man”. It would seem as though condemnation was inevitable, but Paul discusses all the questions of the situation in order to arrive at the significance of the truth, to set it down explicitly, finally, and emphatically, once for all — “There is therefore now, no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus”.

“In Christ Jesus”

The persons under consideration are those are are “IN CHRIST JESUS”. If these are the ones in the conclusion of the argument, then I feel they must be the subjects of the argument itself. It seems to me that Paul’s purpose, therefore, is to show that in spite of the dualism of the believer’s nature and life, he is not robbed of the gracious favour and peace in Christ. At any rate, chapter 7 continues the general subject of chapter 6, that is, the believer’s death with Christ. That is the centre, but chapter 7 brings a new application of the subject. Death with Christ in Rom. 6 is death to sin, but death with Christ in Rom. 7 is death to the law. It is the same death. Dying with Christ means dying to both sin and the law.

At the end of chapter 6 there is the important note of “fruit”: “what fruit had ye then in those things whereof ye are now ashamed?” “Fruit unto holiness”– God looks for fruit unto holiness, and to produce such fruit is one of the purposes of our union with Christ in His death and in His life. When you come to chapter 7 it is clear that the thought of fruit-bearing is in Paul’s mind. He speaks of the failure of the law to produce fruit in human lives, and since the law has failed, there arises a need that we should die to the law, and be joined to another, by Whom this fruit may be produced. That is one reason why we need to get from under the law– its failure, its inability, being weak through the flesh, to fulfil its own requirements, that is, to produce fruit unto holiness. Verses 1 to 3 illustrate the obvious fact that the dominion of the law ends in the death of its subjects. Death closes all accounts, dissolves every bond and every obligation. We will not stay to look at the illustration, but go on to ask, in verse 4, Why should we die to the law? Is there anything wrong with the law? Nothing! Yet it failed to produce holiness in its subjects. The law was never intended to produce it. God knew it could not do so when He sent it. If you want to know why it was sent, and to whom, read 1 Tim. 1:8-10. It was sent, not to make bad men good, but to control their evil. What “in the flesh” means

In verse 5 you have a startling statement — not only was the law unable to produce holiness, but it set in motion the Sin-principle. The law did not create sin, but it did give it energy. That is the undeniable effect of external restraint of any kind upon a sinful nature. In this verse there is a reference to the specific period “when we were in the flesh”. Then it was that the law came in, and gave a new energy to the dormant sin within us. To what time does this refer? The sentence if of ruling importance. If we can understand this we shall understand more. Rom. 8:9 says, “Ye are not in the flesh, but in the Spirit”. What makes the difference? This — the indwelling Spirit resides just where we are. If He dwells in us, then we are “in the Spirit”. If He is not in us, then we are “in the flesh” — we have no union with Christ. That is clear. But in which does the Spirit of Christ dwell? The New Testament teaches that the Holy Spirit dwells in every believer— “Because ye are sons, God hath sent forth the Spirit of His Son into your hearts, crying Abba, Father”. No person is a child of God except the Spirit of God dwells in him, but if the Spirit of God dwells in him, by virtue of that he is a child of God. Walking “after the flesh”

So no child of God can be said to be “in the flesh”. The expression is perfectly unscriptural. But it is possible for a believer, who is not “in the flesh”, to ‘walk after the flesh”, which is quite a different thing. This distinction is important. In verse 5 Paul refers to the state of the unregenerate, when he says, “when we were in the flesh”; but in verse 6 we have a different statement– “But now we have been discharged from the law, having died to that wherein we were holden, so that we serve in newness of the Spirit, and not in oldness of the letter” (R.V.). I do not speak dogmatically, but it seems to me that he refers there to what is taught in Rom. 6: 2-4, “Having died” — died to sin, the sin which holds us — we are “discharged from the law”. You cannot be discharged from the law without being discharged from sin. The former is the consequence of the latter. “That we might serve in newness of spirit, and not in the oldness of the letter.” It is not, as in chapter 6, “newness of life” but, “newness of service”. The former comes by dying to sin, the latter from dying to the law. Fruit unto holiness depends upon serving God. The law stirred up sin rather than holiness, but we must not conclude that it did not serve a necessary purpose. It certainly laid bare forever the exceeding sinfulness of sin. “Sin, that it might appear sin, working death in me by that which is good, that sin … might become exceeding sinful.” Sin is thereby stigmatized as a malignant foe to God, and a ruthless opponent to that which is holy, just and good. What a terrible thing sin must be, that it could slay me through the knowledge of that which is good! That is by far the most difficult part of chapter 7.

The second section begins with verse 14. It is introduced by the statement first, that the law is spiritual; second, I am carnal. We have had that “I” from verse 7, but in verses 14 the “I” has a different content. In verse 7 to 14, the “I” stands for the whole of Paul in his unregenerate state, but in the passage which begins with verse 14, the “I” is used with three different and distinct meanings. That is an indication that we have come to the state of regeneration. There is only one “I” in the unregenerate, but in the regenerate state there are three aspects of the “I”. First, “I” is used as in the preceding section, referring to the whole of Paul’s being. Second, it is used for Paul’s new personality, the new man in Christ, as distinct from the corrupt nature of sin that still clings to part of Paul’s being. Then the third “I” describes just that corrupt nature which is distinct from Paul as the new man in Christ, i.e. (1) “I” as the whole of Paul’s being; (2) The new man in Christ; (3) The “flesh” which still clings to Paul the “new man”. No longer “in the flesh”

Paul, the new man, is no longer “in the flesh”, but the “flesh” is still with Paul. The “I” of verse 14 – “I am carnal, sold under sin” — is just that flesh, the remnants of the old; he is not referring at all to himself as in Christ. The contrast in this verse is between the law and the old nature. The law is spiritual; the old nature, the flesh, the old “I”, is carnal, sold under sin. It is true that the regenerate man sometimes may be “carnal”. We find such in 1 Cor. 3, where Paul says, “Ye are carnal”. They were regenerate, but “carnal” but the carnal of 1 Cor. 3 is very different from the carnal here. In the former the reference is to the nature, the quality. “I am carnal” refers not to himself as the new man, but to the flesh, the old part of him that still clung to him. In chapter 6:18 he says, “Made free from sin” — there is no carnality about the new man — and in chapter 8: 2 he says, “Made free from the law of sin and death”.

Paul makes a statement in verse 14 regarding his present, not his past condition. “The law is spiritual, but I am — not I have been — I am carnal.” That is how he describes that part of him which is “flesh”, in its nature the devoted slave of sin, sold as in a slave market, a veritable creature of sin. That is the flesh! The law is spiritual, but I am carnal. They are right opposites. The flesh is enmity against God, but the law is spiritual. That is the language, not of an ungodly man, nor of a carnal Christian, it is the language of a spiritual Christian referring, of course, not to the “new man” in Christ, but to the flesh, the other nature that is still existent. The conflict in the believer is between that which is redeemed already, and that which remains unredeemed, and which is, in fact, irredeemable — the flesh.

When we are regenerated by the Holy Spirit, the change thus wrought works in the heart, the will, and the spirit, but it effects no kind of change in the flesh. The flesh is still the same. Verse 15 shows that there is perpetual conflict, “for that which I do I allow not”. There are five uses of the pronoun “I” in this verse – three really, with two repeated. “That which I (the flesh) do, I (the new man) allow not; for what I (the new man) would, that I (Paul as a whole) do not; but what I (the new man) hate, that I (the flesh) do.” You cannot give the same content to the pronoun each time it is used, that is impossible. Manifestly there is a duality in the redeemed believer. It is a picture of the sad disunity in a believer’s being, while he waits, groaningly sometimes, but always rejoicingly, for the redemption of his body, when that duality will cease.

Again in verse 15, ” That which I do I allow not “–” I know not ” (R.V.) probably, ” I sanction not, I approve not, I acknowledge not, I own not “. I, the new man, do not acknowledge at all, what is not mine, because it is contrary to my purpose and choice. That is the crux of the whole thing. Paul is not bemoaning himself as in a hopeless state, and his life as futile. He is on his way to Rom. 8. I, and he is pointing out the duality, resulting, of course, in a very sad handicap, but with that goal always in view. The flesh is there, it seriously hinders and vexes, but it has not the upper hand, for I do not recognize what the flesh does as my own act, when my choice is against it. Please do not think Paul is speaking of vices and crimes that his ” flesh ” was doing–not at all. He was a man of sublime ideals, but “What the flesh is and involuntarily does, I allow not “. The new man would not own it as his. When we come to the Lord for salvation, the sins we confess are our own, but when we have come to Christ, and DIED UNTO SIN WITH HIM, and pursue a path of holiness, and when the ” new man ” does not in any way truck with the flesh, and ally itself with it–then the ” flesh ” may act involuntarily, when it becomes a matter of actively disowning it. It is absolutely essential. Between the new man and the ” flesh ” there is the separation of the Cross of Christ. God has set the new man free. The ” flesh ” is the ” flesh ” and ” in me, that is in my flesh, dwelleth no good thing “. [ These ” involuntary ” workings of the ” flesh ” become more clearly recognized by the ” new man ” as he is being ” renewed in knowledge after the image of Him that created Him ” (Col. 3: 10). He cannot ” refuse ” what he does not discern, but as he walks in the light (Ephes. 5: 13) of God, he is responsible ” put to death ” the ” doings of the body” (Rom. 8:13) by the Spirit, continuously. (See also Gal. 5.:16-26).] “No more ‘I'”

Verse 17 is a bold inference. May the Lord give us courage to make it ! Since that is the case, ” if then I do that which I would not … It is no more I that do it “–read it in its bare simplicity–“but sin that dwelieth in me” It is no more I ! Are you sure, Paul, that ” sin dwelleth ” in you ? There is no man under heaven, alas, of whom that statement is not true. Paul distinguishes sharply between himself, the new man, and indwelling sin. His whole will is against any of the involuntary actions of the ” flesh “. He is not the do-er by his own deliberate choice.

John says explicitly that he that is born of God cannot sin. I do not know whether there is a place for that verse in your doctrine or not, but it is Scripture. At the same time, you find place for that in your doctrine, you must find for this also, ” If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves “. When a conflict of theories comes, it arises out of the fact that one school leaves out one verse, and the other school leaves out the other ! To have a Scriptural doctrine you must find place for all the verses that have anything whatever to say on the matter. The ” new man ” cannot do anything but delight in the law of God–if it could it would need salvation, and I do not know of any salvation for the new man in Christ.

Paul says ” I delight in the law of God after the inward man”, but there is the other side–” I see another law in my members … the law of sin which is in my members”. Here are two bents, the bent of the inner man and the bent of sin, in other words, the bent of the body, or sin in the members. Sin is everywhere in the body–in its members, in its faculties, in its organs, sin penetrating all the mechanism of its being.

Everywhere it is ready to stir up illegitimate appetites and desires. It is very clear to me that Paul did not expect deliverance from this duality and conflict until he was clothed with a new body. All the trouble, he makes clear, is centred in the body of sin [ This is clear from the Greek word ” kartargeo “, rendered ” destroy ” in Rom. 6:6. The Lexicon says it means ” To leave unemployed. To make barren, void, useless ” i.e, the ” doings of the body ” are inoperative through the continuous reckoning of the fact that “our old man was crucified with Christ”. See verses 11-12, ” Let not sin reign in your dying body ” (Conybeare).] ; the body of death, because it is a body of sin, and sin involves the body in death.

Do not forget that he was rejoicing in hope too. Do not be afraid of these paradoxes, for therein you get the full truth. Standing in grace, and rejoicing in hope of the glory of God and yet groaning in himself, and waiting to be clothed upon with his ” house not made with hands “. He had a redeemed will, heart and mind, in a measure, but he wanted a redeemed body. Don’t you? That hope of the consummation was such an exulting one that as he thought about it he burst out with a ringing Hallelujah ! ” I thank God through Jesus Christ our Lord ! “