“There remaineth therefore a rest to the people of God.” HEBREWS 4:9

THE keynote of this chapter is Rest. In the second verse it is spoken of as a gospel, or good news. And is there any gospel that more needs preaching in these busy, weary days, through which our age is rushing to its close, than the Gospel of Rest? On all hands we hear of strong and useful workers stricken down in early life by the exhausting effects of mental toil. The tender brain tissues were never made to sustain the tremendous wear and tear of our times. There is no machinery in human nature to repair swiftly enough the waste of nervous energy which is continually going on. It is not, therefore, to be wondered at that the symptoms of brain tiredness are becoming familiar to many workers, acting as warning signals, which, if not immediately attended to, are followed by some terrible collapse of mind or body, or both.

And yet it is not altogether that we work so much harder than our forefathers; but that there is so much more fret and chafe and worry in our lives. Competition is closer. Population is more crowded. Brains are keener and swifter in their motion. The resources of ingenuity and inventiveness, of creation and production, are more severely and constantly taxed. And the age seems so merciless and selfish. If the lonely spirit trips and falls, it is trodden down in the great onward rush, or left behind to its fate; and the dread of the swoop of the vultures, with rustling wings, from unknown heights upon us as their prey, fills us with an anguish which we know by the familiar name of care. We could better stand the strain of work if only we had rest from worry, from anxiety, and from the fret of the troubled sea that cannot rest, as it moans around us, with its yeasty waves, hungry to devour. Is such a rest possible?

This chapter [Hebrews 4] states that such a rest is possible. “Let us labor therefore to enter into that rest [v.11]” Rest? What rest? His rest, says the first verse; my rest, says the third verse; God’s rest, says the fourth verse. And this last verse is a quotation from the earliest page of the Bible, which tells how God rested from all the work that he had made [Gen. 2:2,3]. And as we turn to that marvelous apocalypse of the past, which in so many respects answers to the apocalypse of the future given us by the Apostle John, we find that, whereas we are expressly told of the evening and morning of each of the other days of creation, there is no reference to the dawn or close of God’s rest-day; and we are left to infer that it is impervious to time, independent of duration, unlimited, and eternal; that the ages of human story are but hours in the rest-day of Jehovah; and that, in point of fact, we spend our years in the Sabbath-keeping of God. But, better than all, it would appear that we are invited to enter into it and share it; as a child living by the placid waters of a vast fresh water lake may dip into them its cup, and drink and drink again, without making any appreciable diminution of its volume or ripple on its expanse…

This, then, is the rest which we are invited to share. We are not summoned to the heavy slumber which follows over-taxing toil, nor to inaction or indolence; but to the rest which is possible amid swift activity and strenuous work; to perfect equilibrium between the outgoings and incomings of the life; to a contented heart; to peace that passeth all understanding; to the repose of the will in the will of God; and to the calm of the depths of the nature which are undisturbed by the hurricanes which sweep the surface, and urge forward the mighty waves. This rest is holding out both its hands to the weary souls of men throughout the ages, offering its shelter as a harbor from the storms of life…

And there is yet a further reason for this conviction of God’s unexhausted rest. Jesus, our Forerunner and Representative, has entered into it for us. See what verse 10 affirms: “He that is entered into his rest; ” and who can he be but our great Joshua, Jehovah-Jesus? He also has ceased from his own work of redemption, as God did from his of creation. After the creative act, there came the Sabbath, when God ceased from his work, and pronounced it very good; so, after the redemptive act, there came the Sabbath to the Redeemer. He lay, during the seventh day, in the grave of Joseph, not because he was exhausted or inactive, but because redemption was finished, and there was no more for him to do. He sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on High; and that majestic session is a symptom neither of fatigue nor of indolence. He ever liveth to make intercession; he works with his servants, confirming their words with signs; he walks amid the seven golden candlesticks. And yet he rests as a man may rest who has arisen from his ordinary life to effect some great deed of emancipation and deliverance; but, having accomplished it, returns again to the ordinary routine of his former life, glad and satisfied in his heart.

Nor is this rest for Christ alone; but for us also, who are forever identified with him in his glorious life. We have been raised up together with him in the mind and purpose of God, and have been made to sit with him in the heavenlies; so that in Jesus we have already entered into the rest of God, and have simply to appropriate it by a living faith [Eph. 2:4-7].

How, then, may we practically realize and enjoy the rest of God?

1. We must will the will of God. So long as the will of God, whether in the Bible or in providence, is going in one direction and our will in another, rest is impossible. Can there be rest in an earthly household when the children are ever chafing against the regulations and control of their parents? How much less can we be at rest if we harbor an incessant spirit of insubordination and questioning, contradicting and resisting the will of God! That will must be done on earth as it is in heaven. None can stay his hand, or say, What dost thou? It will be done with us, or in spite of us. If we resist it, the yoke against which we rebel will only rub a sore place on our skin; but we must still carry it. How much wiser, then, meekly to yield to it, and submit ourselves under the mighty hand of God, saying, “Not my will, but thine be done!” The man who has learned the secret of Christ, in saying a perpetual “Yes” to the will of God; whose life is a strain of rich music to the theme, “Even so, Father”; whose will follows the current of the will of God, as the smoke from our chimneys permits itself to be wafted by the winds of autumn, that man will find rest unto his soul.

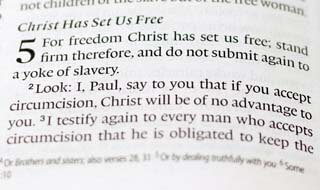

2. We must accept the finished work of Christ. He has ceased from the work of our redemption, because there was no more to do. Our sins and the sins of the world were put away. The power of the adversary was annulled. The gate of heaven was opened to all that believe. All was finished, and was very good. Let us, then, cease from our works. Let us no longer feel as if we have to do aught, by our tears or prayers or works, to make ourselves acceptable to God. Why should we try to add one stitch to a finished garment, or append one stroke to the signed and sealed warrant of pardon placed within our hands? We need have no anxiety as to the completeness or sufficiency of a divinely finished thing. Let us quiet our fears by considering that what satisfies Christ, our Saviour and Head, may well satisfy us. Let us dare to stand without a qualm in God’s presence, by virtue of the glorious and completed sacrifice of Calvary. Let us silence every tremor of unrest by recalling the dying cry on the cross, and the witness of the empty grave.

3. We must trust our Father’s care. “Casting all your care upon him, for he careth for you [1 Pet. 5:7].” Sometimes like a wild deluge, sweeping all before it, and sometimes like the continual dropping of water, so does care mar our peace. That we shall some day fall by the hand of Saul; that we shall be left to starve or pine away our days in a respectable workhouse; that we shall never be able to get through the difficulties of the coming days or weeks; household cares, family cares, business cares; cares about servants, children, money; crushing cares, and cares that buzz around the soul like a swarm of gnats on a summer’s day, what rest can there be for a soul thus beset? But, when we once learn to live by faith, believing that our Father loves us, and will not forget or forsake us, but is pledged to supply all our needs; when we acquire the holy habit of talking to him about all, and handing over all to him, at the moment that the tiniest shadow is cast upon the soul; when we accept insult and annoyance and interruption, coming to us from whatever quarter, as being his permission, and, therefore, as part of his dear will for us, then we have learned the secret of the Gospel of Rest.

4. We must follow our Shepherd’s lead. “We which have believed do enter into rest” (Heb. 4:3). The way is dark; the mountain track is often hidden from our sight by the heavy mists that hang over hill and fell; we can hardly discern a step in front. But our divine Guide knows. He who trod earth’s pathways is going unseen at our side. The shield of his environing protection is all around; and his voice, in its clear, sweet accents, is whispering peace. Why should we fear? He who touches us, touches his bride, his purchased possession, the apple of his eye. We may, therefore, trust and not be afraid. Though the mountains should depart, or the hills be removed, yet will his loving kindness not depart from us, neither will the covenant of his peace be removed. And amid the storm, and darkness, and the onsets of our foes, we shall hear him soothing us with the sweet refrain of his own lullaby of rest: “My peace I give unto you; in the world ye shall have tribulation, but in me ye shall have peace [John 16:33].”

This is an excerpt from Meyer’s commentary on Hebrews. The book is available from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library at Calvin College (http://www.ccel.org). Bracketed references added.

Frederick Brotherton Meyer (April 8, 1847 – March 28, 1929), a contemporary and friend of D. L. Moody and A. C. Dixon, was a Baptist pastor and evangelist in England involved in ministry and inner city mission work on both sides of the Atlantic. Author of numerous religious books and articles, many of which remain in print today, he was described in an obituary as The Archbishop of the Free Churches.