[Annotated edition; bold, colors and bracketed content added. Pages numbers from the CLC edition]

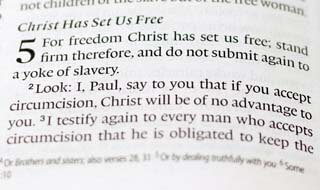

“There is therefore now no condemnation to those who are in Christ Jesus, who do not walk according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit. for the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has made me free from the law of sin and death.” – Rom. 8:1, 2

“Without Me you can do nothing.” – John 15:5

“I can do all things through (in) Christ who strengthens me.” – Phil. 4:13

“Be strong in the grace that is in Christ Jesus.” – 2 Tim. 2:1

TO UNDERSTAND the full meaning of the privilege “no condemnation,” we must know what is meant by the term “in Christ Jesus.” The phrase “in Christ” is almost peculiar [unique] to St. Paul. It occurs in his epistles alone about seventy-eight times. But the germ [essence] is found in the words of our Lord: “Abide in Me, and I in you” (John 15.:4).

A careful examination of the various passages will show us that the truth expressed in the words “in Christ” has two distinct aspects – the one referring to justification, the other to sanctification. While we would distinguish one from the other, we would not separate them. There is what we may term the “in Christ” of standing, and the “in Christ” of walk or experience. The former has reference to headship, the latter to fellowship.

Headship. Each of us occupies one of two positions – Adam or Christ. God’s dealings have reference to two men – the first and the last Adam. The whole human race was headed up in Adam. We must not regard humanity as so many separate individuals – like a heap of sand – but as an organic unity – like a tree – though consisting of an innumerable number of parts, yet forming one whole.

42

In Adam, then, we see the whole family of man summed up; and there, in him, we see the whole race on its trial.

Adam’s trial was man’s probation. It was not the trial of a single individual, it was the trial of the whole human race. All were included in him. His fall was the fall of the whole family. “as through one man sin entered the world, and death through sin, and thus death spread to all men, because all sinned.” (“All sinned” (aorist tense) i.e., in Adam. Probation may be looked at either as having reference to salvation or to service. Probation so far as salvation is concerned is no longer a question of our own works. In that sense our [legal] probation terminated with Adam’s failure. But probation in connection with service is still going on. And it is in that sense that we must understand the apostle as writing when he says, “lest that by any means, when I have preached to others, I myself should be a castaway,” or “should be rejected” (R.V.) – (1 Cor. 9:27) – disproved or rejected, that is, as to service.)

There we have the end of the trial. That terminates, strictly speaking, human probation (Rom. 5:12).

It is to such that the Gospel comes. Not to those whose trial is undecided, who are in process of being tested, who are still on probation; but to those whose opportunity on that ground is forever gone – to those, therefore, who are “lost.”

And what does the Gospel propose? Does it come proposing another trial? Does it come offering to put man on a second probation? Nothing of the sort. The burden of its message [the Gospel] is not probation, but redemption.

43

Take an illustration. Here is a tree with numerous branches. Cut the root, and what happens? Death; it not only enters into the stem, it passes over the whole tree, it affects each branch, and every leaf.

To propose the improvement of the old position in Adam, is like the vain effort of endeavouring to revive the life in the separate branches of the dead tree.

The Gospel proclaims a new creation: a new tree – union with a new root – being grafted on to a new stock. “If any man be in Christ, he is a new creature” (2 Cor. v. 17). This is not to improve the old, but to be translated into a new position.

Take another illustration. Here is a man, let us suppose, who has failed in business. He is not only hopelessly insolvent, his credit is gone, and his name is disgraced. All efforts of his own to retrieve his position are utterly fruitless; he is beyond all hope of recovery in that direction. But hope comes to him from another quarter. Let us suppose he is taken into partnership by one whose name stands high in the commercial world. He becomes a partner in a wealthy and honourable firm. All his debts are paid by that firm, and the past is cancelled. But this is not all. He gets an entirely new standing. His old name is set aside, forgotten, buried for ever. He has now a new name [new identity]. In that name he transacts all his business. His old name is never again mentioned.

We have here a faint shadow of what the Gospel bestows. To be a believer in Christ is to have passed out of our old position – to lose our old name – and to take our stand on an entirely new ground. We are baptized “into the name of the Lord, ” – we are “in Christ.”

44

“There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus” [Rom. 8:1]. This is not a privilege that comes to the believer by degrees; it is complete and absolute at once. And the moment the transition takes place, the believer stands, not on the ground of probation, but on the ground of redemption.

This truth is fundamental. The “in Christ” of standing is the foundation of all practical godliness, of all Christian service. We must start here, or we cannot take a single step in the way of holiness.

But this does not exhaust the meaning of the phrase “in Christ”; nor is this all that is to be understood by the Apostle’s declaration in the opening words of this eighth chapter of his Epistle to the Romans. Included in this statement is also the thought of –

Fellowship. To be “in Christ” in this sense is to have the consciousness of His favour. This is a matter, not of standing, but of experience – and yet not of feeling, but of faith. We are commanded to “abide” in Christ. That which has reference to our judicial standing cannot be a matter of exhortation. Those who have taken their stand in Christ – who are justified – are now required to remain, to dwell, or abide in Him for sanctification. The “in Christ” which has to do with our experience and walk, which relates to our sanctification, is constantly a matter of exhortation in the Scriptures.

It is possible, alas! not to abide in Him. And what happens when the believer ceases to abide? He then lives the self-life.

There is such a thing as a religious self-life [walking after the flesh]. Is it not the life that is too often manifested, even by those who have a saving knowledge of Christ?

45

There may be a clear apprehension of what it is to be “in Christ” as to justification, and yet much darkness and perplexity as to the “in Christ” of sanctification. Many have a true aim, seeking to glorify Christ, and to be made like Him; they have sincere and earnest desires, and they are making constant and vigorous efforts after holiness; and yet they are continually being disappointed. Failure and defeat meet them at every turn. Not because they do not try, not because they do not struggle, – they do all this, – but because the life they are living is essentially the self-life and not the Christ-life.

They are brought into [subjective] condemnation. This arises from the fact that the “law of sin” in their members [Rom. 7:21,23] is stronger than their renewed nature [the regenerated human spirit].

The soul that ceases to abide in Christ lives the “I myself” life. The words, “them which are in Christ Jesus,” form a contrast to the expression, I as I am in myself, in the seventh chapter, twenty-fifth verse (Godet).

“I myself” – “apart from and in opposition to the help which I derive from Christ” (N. T. Commentary, edited by Bishop Ellicott) – I myself am conscious of a miserable condition of internal conflict, between two opposite tendencies – the two natures: the one consenting to the law that it is good, delighting in it, and desiring to fulfill its requirements; the other drawing me in the contrary direction, and; being the more powerful of the two, actually bringing me into captivity to the law of sin, and thus resulting in a condition of condemnation. [1]

“I in myself.” “This expression is the key to the whole passage (Rom. 7:14 – 25).

46

St. Paul, from verses 14 to 24, has been speaking of himself as he was in himself.” (Conybeare and Howson.)

“There is therefore now no condemnation.” “This word no (Greek aucune),” as Professor Godet observes, “shows that there is more than one sort of condemnation, resting on the head of him who is not in Christ Jesus. There is, first, the Divine displeasure excited by the violation of the law [objective] – the anger described in the first three chapters of the Epistle to the Romans. The two following chapters represent to us the removal of this condemnation by the blood of Christ, and by the faith that consents to come and draws its pardon thence.

“But if, [secondly] after this, sin continues the master of the soul, [subjective] condemnation will infallibly revive. For Jesus did not come to save us in sin, but from sin. It is not pardon which constitutes the health of the soul, it is salvation, it is the restoration of holiness. The reception of pardon does not affect our resemblance to God; holiness alone does this. Pardon is the threshold of salvation, the means by which convalescence is begun. Health itself is holiness.

“If then, the first condemnation to be taken away is that of sin as a fault, the second, which must necessarily be removed too in order that the first may not return, is sin as a power, as the inwrought tendency of the will. And it is the removal of this second condemnation that St. Paul here describes: ‘for the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has made me free from the law of sin and death.'”[Rom. 8:2]

In this “I myself” life, the evil tendency gains the ascendancy. So that though with the new nature, the inner man, or the mind, we serve the law of God,

47

yet we are nevertheless overcome, and are practically brought into captivity to the law of sin. Such a life must of necessity be a life of condemnation in the daily experience.

But another characteristic belongs to this self-life. It is essentially carnal (Greek sarkikos) (Rom. 7:14. See Appendix Note B), not carnal in the sense of being unregenerate. A carnal man may be also one who has been born of the Spirit, but is not sufficiently actuated by His enlightening and sanctifying power to overcome the hostile power of the flesh; he still thinks, feel, judges, acts, “according to the flesh” (Lange’s Comm. on 1 Cor. 3:1).

The condition described by “carnal” may be either the immature stage of the young convert, or a state of relapse into which the more advanced believer has fallen. To the first no blame can be attached, for all must pass through this stage in their progress from the natural to the spiritual. But to the second [subjective] condemnation belongs, as we see from the way in which the Apostle writes to the Corinthian believers, “I could not speak unto you as unto spiritual, but as unto carnal, even as unto babes in Christ” (1 Cor. 3:1).

“He is here [in 1 Cor. 3:1-4] not speaking of Christians as distinguished from the world, but of one class of Christians as distinguished from another” (Hodge).

This is the description of every believer, even an apostle, regarded as he is in himself [in the mortal body]. And such is the experience of the believer when he lives out of fellowship with Christ [walking according to the flesh]. The carnal or fleshly principle gains the ascendancy. [When living in a carnal condition, the believer…]

48

He is no longer spirit, soul, and body, but rather body, soul, and spirit, the order being reversed, the lowest principle becoming dominant.

To be “in Christ” as to fellowship is to have the individual human spirit apprehended, or laid hold of, by the Holy Spirit of God. We are thus not only brought into harmony with God, but linked with the power of God. The ability we lack when we struggle to overcome in the self-life is no longer lacking in the Christ-life. This is to be free from the law of sin and death – this is to be spiritually-minded [Rom. 8:2; Phil. 2:5].

The following remarks by an able and distinguished theologian are well worthy of careful perusal. “We maintain now, as ever, that even in Romans 7:14 – 24, Paul is speaking ‘out of the consciousness of the regenerate person,’ without thereby meaning to say that he is giving utterance to experiences which are permitted to the regenerate as such – rather experiences which even the regenerate person is not spared. It certainly appears an irreconcilable contradiction to say that one and the same man is fleshly, sold unto sin (Rom. 7: 14), and yet, on the other hand, is free from the law of sin and death by the Spirit of life that is in Christ Jesus (Rom. 8:2).

“But the Apostle actually places the two states in juxtaposition, as belonging to his present condition. He does not say in chap. 7:14 that he was previously consisting of fleshly material, and was sold under sin, but that this is his natural constitution [all believers continue to have the “flesh” in them], and that this contrariety subsists between him and God’s spiritual law. He speaks in the present; and when he sets forth, in continuation, that his acknowledgement of the law [of God] does not help him to do the prescribed good, but that sin, in spite of his own will, makes him do that which is against God’s will, he speaks throughout in the present.

49

“This established present claims to be all the more considered, that the Apostle (chap. 7:7 – 13) also actually speaks in historical form of a fact of experience which at that time belongs to the past. He looks back there into his childhood, and shows how, in the degree that the claim of law entered into his consciousness, the sin which was present in him, but not present as his personal conduct, became his personal sin, and the cause of his self – incurred death. It was the saving purpose of the law declared in verse 13 which he thus painfully experienced [the law is a school master to lead us to Christ, Gal. 3:24]. From verse 14 onwards, the Apostle then depicts how he, the self-consciously willing one, finds himself [a saved person] and his doing disposed in the light of the law. Every Christian is compelled to confirm what the Apostle here says, from his own personal experience. And well for him if he can also confirm the fact that God’s law, and therefore God’s will, is his delight [Rom. 7:22], – that he desires the good and hates the evil; and, indeed, in such a way that the sin to which, against his will, he is hurried away, is foreign to his inmost nature [his/her regenerated spirit]. But woe to him, if from his own personal experience he could only confirm this, and not also the fact that the Spirit of the new life that has its source in Christ Jesus, has freed him from the urgency of sin, and the condition of death, which were not abrogated through the law, but only brought to light; so that his will, which by the law was inclined towards what is good, although powerless, now actually capable of good, is opposed [victorious over], (as a predominating, overmastering power of life, which will finally triumph in glory), to the death that continues to work in him” (Delitzsch, System of Biblical Psychology, pp. 453 – 455).

50

But it has been objected, “if I am in Christ, and am depicting that which I am out of Christ, I depict in concreto, not what I actually am, but what I once was out of Christ” (the view of commentator, Philippi).

Now, as Delitzsch observes, it is only necessary to look into one’s own heart to see at once what a sophism [foolish objection] this is. Every man who is in Christ knows from actual experience what it is to be out of Christ in his walk and life. Every believer knows from sad experience what it is to cease to abide in Christ. Not that it is possible to live both lives at one and the same time – that is to be in Christ as to fellowship, and out of Christ in the same sense, at any one moment. The objection urged is based upon the assumption that the term “in Christ” can be understood only in one sense. But the twofold sense of the phrase [in Christ], or the double aspect of the truth, is what we have endeavoured to elucidate.

It is the believer’s privilege to know that there is now no condemnation for him, whether he thinks of himself as standing before God as a Judge, or as walking before God as a Father. As in the one case he stands before God in Christ the Righteous One, who has met all the claims of the righteous law; so in the other he is abiding in Christ the Holy One, who has satisfied all the desires of a Father’s heart.

Thus walking, he knows the blessedness of pleasing God. Surely it is to this condition of soul that the Apostle refers when he says, “Beloved, if our heart condemn us not” (1 John 3:21) – not if we stand justified in Christ [objectively], but if our heart be not accusing us [subjectively] – “we have confidence towards God.”

51

It is worthy of note that while the Apostle in those eleven verses (Rom. 7:14 – 24) refers to himself, either directly or indirectly, some thirty times, he does not there make a single reference either to Christ or the Holy Spirit. In reading that passage it is not necessary to suppose that the Apostle is speaking from the standpoint of a present experience, but from the standpoint of a present conviction, as to the tendencies of the two natures that were then and there present within him.[1]

The freedom of which the Apostle speaks in the opening words of the eighth chapter [of Romans], he enforces by an inference and a reason. The inference or conclusion is indicated by the word “therefore.” “There is therefore now,” etc. But to what point in the argument does this note of inference refer? To what does it go back? A careful perusal shows us that this first verse is a conclusion springing out of the first six verses of the seventh chapter.

Three great truths he had put before his readers: substitution, identification, and union. The thought of substitution he unfolds in chap. 5.: “Christ died for the ungodly,” “Christ died for us,” verses 6 and 8 (see Appendix Note A). Here, too, we have the headship of the first and second representatives, Adam and Christ, dwelt upon.

The thought of identification he brings out in chap. 6. The believer is there regarded as crucified and buried with Christ. See verses 6 and 4.

And then there is the thought of union. It is in the opening portion of chap. 7 that this truth is set forth. “You also have become dead to the law through the body of Christ, that you may be married to another” [Rom. 7:4].

52

This truth is dwelt on only in the first six verses. At the seventh verse a digression begins, and the subject of union is not again taken up until the first verse of chap. 8. The progress of thought in these three great facts – substitution, identification, and union – is indicated in the prepositions “for,” “with,” and “in.” It has been said with truth, an immense amount of divinity is contained in the prepositions of the New Testament.

“Therefore now in Christ Jesus” – being brought into union with Him, not judicially alone, but experimentally also – “there is no condemnation.”

But the Apostle assigns a reason for this blessed state of things, in these words. “For the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has made me free from the law of sin and death” [Rom. 8:2]. By this union we are brought into a condition of deliverance. We get the benefit of a liberating power. Redemption then is realized to be an emancipation from sin, not merely by virtue of an act done in the past, but by virtue of a law [principle] which is in force in the present – of a law which never ceases to be in force. One law is, in fact, being effectually counteracted by another law. Fellowship with Christ, union of heart and mind with Him, introduces the soul into that sphere where all the benefits of this victorious law become his. It is there, “in Christ Jesus,” but only there, that this blessed freedom can be known and realized.

What we are out of that sphere, we see as in a [looking] glass in those eleven verses in chap. 7; but what we are in Him – within the circle of His presence, we learn from chap. 8

The believer is thus reminded of the truth of that terse but pregnant sentence spoken by the Lord Himself:

53

“Without Me,” or apart from Me, “you can do nothing” (John 15:5); that is, without fellowship with Me, even after you have been brought to know Me as your Lord and Saviour. “It is a poor and inadequate interpretation of the words ‘without Me’ to make them to mean ‘You can do nothing until you are in Me, and have My grace.’ It is rather, ‘After you are in Me, you can even then accomplish nothing, except you draw life and strength from Me. From first to last it is I that must work in and through you'” (Trench).

[illustration] If a piece of iron could speak, what could it say of itself? “I am black; I am cold; I am hard.” But put it in the furnace, and what a change takes place! It has not ceased to be iron; but the blackness is gone, and the coldness is gone, and the hardness is gone! It has entered into a new experience. The fire and the iron are still distinct, and yet how complete is the union – they are one. If the iron could speak, it could not glory in itself, but in the fire that makes and keeps it a bright and glowing mass. So must it be with the believer. Do you ask him what he is in himself? He answers, “I am carnal, sold under sin” [Rom. 7:14]. For, left to himself, this inevitably follows; he is brought into captivity to the law of sin which is in his members. But it is his privilege to enter into fellowship with Christ, and in Him to abide. And there, in Him, who is our life, our purity, and our power – in Him, whose Spirit can penetrate into every part of our being, the believer is no longer carnal, but spiritual; no longer overcome by sin and brought into captivity, but set free from the law of sin and death, and preserved in a condition of deliverance.

54

This blessed experience of emancipation from sin’s service and the power implies a momentary and continuous act of abiding.

The believer cannot glory in himself. He cannot glory in a state of purity attained, and having an existence apart from Christ Himself. He is like the piece of iron. The moment it is withdrawn from the furnace, the coldness and hardness and blackness begin to return. It is not by a work wrought in the iron once for all, but by the momentary and continual influence of the fire on the iron that its tendency to return to its natural condition is counteracted.

Such is the law of liberty in the spiritual life. We can thus understand how there may be a continuous experience of deliverance from the law of sin, and at the same time a deepening sense of our own natural depravity – a life of triumph over evil with a spirit of the truest humility.

The following is an extract from Bishop Ellicott’s New Testament Commentary for English Readers, on the opening words of Romans 8:

- “It [Romans ch. 8] differs from the first section of chapter 5. in this, that while both describe the condition of the regenerate Christian, and both cover the whole range of time from the first admission to the Christian communion down to the ultimate and assured enjoyment of Christian immortality, chapter 5. lays stress chiefly on the initial and final moments of this period, whereas chapter 8 emphasizes rather the whole intermediate process. In technical language, the one [ch. 5] turns chiefly upon justification, the other [ch. 8] on sanctification.“

- Dr. Lange on the same passage remarks in his commentary:

55

“The question of the reference to justification or sanctification must affect the interpretation of condemnation [in Rom. 8:1], since verse 2, beginning with gar [Greek “for”] seems to introduce a proof. The position of the chapter in the epistle, as well as a fair exegesis of the verses, sustain the reference to sanctification. (Not to the entire exclusion of the other, any more than they are sundered in Christian experience) – We must then take no condemnation in a wide sense.”

[1] On a more precise way of defining the believer’s “two natures”, see

https://gracenotebook.com/does-the-believer-have-two-natures/

For further study on the distinction between relationship and fellowship, see this article: Relationship and Fellowship_JBW