BIBLICAL WORD STUDIES

The Role of Word Studies

Scholars have been emphatic about the limitations of the Bible as a source book for a system of biblical psychology. An example of this reluctance is the analysis of G. C. Berkouwer, as translated by Anthony Hoekema:

“In the general judgment [of theologians] is that the Bible gives us no scientific teaching about man, no “anthropology” that would or could be in competition with a scientific investigation of man in the various aspects of his existence or with philosophical anthropology.” [9]

Others point out that the Scriptures do not use scientific language; that essential words about man’s makeup are used somewhat interchangeably. While sharing this reluctance to define a formal system of biblical psychology, conservative scholars acknowledge that the Bible’s teaching is authoritative in clarifying every topic, including this one. Although the Bible does not purport to be a science textbook, the nature of verbal plenary inspiration requires the believing scholar to accept its teaching as authoritative; this includes both scientific and religious areas.

8

As J. I. Marais put it,

“A reverent study of Scripture will undoubtedly lead to a well-defined system of psychology [the study of the immaterial part of man], on which the whole scheme of redemption is based. “[10]

In the process of investigating Scriptural teaching on topics such as the makeup of human beings, the discipline of biblical word studies is foundational. William Barclay once affirmed,

“The more I study words, the more I am convinced of their basic and fundamental importance. On the meaning of words everything depends. No one can build up a theology [or psychology] without a clear definition of the terms which are to be used in it. . . Christian belief and Christian action both depend upon a clear understanding of the meaning of words.” [11]

This study of essential vocabulary will depend upon the material in Hebrew and Greek lexicons and concordances. Etymology of ancient words is helpful, but usage is just as important in determining accurate definitions.

Terms Used for the Body

The primary word for the physical body of living things in the Old testament is basar. It occurs over 250 times in the Hebrew Bible almost always translated “flesh.” Basar is used of the body of man corporately and individu-ally (Deut 5:26; Num 8:7). When God created Eve, he used

9

part of Adam’s “flesh” (Gen 2.21), and their sexual rela-tionship was described as being ones “flesh.” Basar sometimes refers to kindred relationships, as when Joseph’s brothers decided not to kill him since he was their brother, i.e. their “flesh” (Gen 37:27). In Gen 6:3 God announced “My Spirit shall not strive with man forever, for he is indeed flesh; yet his days shall be one hundred and twenty years.” Such contexts implies mankind as frail, having a tendency to stray from God (Gen 6:12). The Psalmist contrasted the limitations of man’s attacks (against his enemy’s flesh) with the sufficiency of God’s strength (Ps 56:4).

The body of flesh was sometimes differentiated from man’s mortal life. Job anticipated his bodily resurrection: “And after my skin is destroyed, this I know, That in my flesh I shall see God” (Job 19:26). God contrasts His nature with that of basar in Isa 31:33: Now the Egyptians are men, and not God; And their horses are flesh, and not spirit. . . ” In Num 16:22, the LORD is called “the God of the spirits of all flesh.” Thus the physical body of man is often referred to in the Old Testament, yet without limiting him to a material nature. Additional terms used less frequently in the Old Testament could be mentioned, but since there are about 80 different Hebrew terms for the body and its members, the above word studies will suffice.

The most basic term in the New Testament for the body is soma, which occurs some 146 times. Soma can also be used of plant, animal, or celestial bodies (Heb 13:11;

10

1 Cor 15:37, 40). Metaphorically, it can describe the spiritual union of true believers as “the body” of Christ (Rom 12:5). It is also used of the elements of the bread and wine in the Lord’s Supper, when Christ called them “My body” (Matt 26:26).

The use of soma for man’s body avoids Greek notions of the innate inferiority of matter. As B. O. Banwell observed,

“The N.T. usage of soma, “body,” comes close to the Hebrew and avoids the thought of Greek philosophy, which tends to castigate the body as evil, the prison of the soul or reason, which was seen as good.” [12]

For example, “the Lord is for the body” (1 Cor 6:13); husbands are expected to love their wives as their own bodies (Eph 5:28), and food should be given to satisfy the hunger of the body (Jas 2:16). Evil comes from the heart, not just from bodily appetites (Luke 6:45). Nevertheless, the freedom of man’s will, the pressures of a sinful society, demonic influence, and the flesh conspire to make the mortal body of fallen man a source of continual vulner-ability and temptation (Rom 6:12). The way to godliness requires self-discipline but not asceticism (1 Cor 9:27; Col 2:23). Physical pleasure within the boundaries of God’s design are credited as His gifts (1 Cor 7:14; 1 Tim 6:17). The body of the believer in Christ has special dignity as the temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor 6:19).

11

The use of soma indicates that the body is an integral part of man, yet distinct from his immaterial part. In Rev 18:13 body and soul together describe man. Jesus affirmed the contrast of these two elements in Matt 10:28: “And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. But rather fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell.” In 2 Cor 12:2,3, Paul distinguished these parts of man as separable and distinct.

“I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago–whether in the body I do not know, or whether out of the body I do not know, God knows–such a one was caught up to the third heaven. And I know such a man–whether in the body or out of the body I do not know, God knows . . .”

James notes that faith without works is dead even as the physical body without the spirit is dead (Jas 2:26).

The other major word used in the New Testament to describe the human body is sarx. Appearing about 150 times in the text, its primary meaning is “flesh”; approxi-mating the meaning of the Hebrew word basar. It is used to denote the flesh of animals and man (1 Cor 15:39). Sarx can be ethically neutral, referring to man’s material nature, or of social status (1 Cor 1:26; Eph 6:5). It is also used to denote heredity (Rom 9:3), Christ’s incarna-tion (1 Tim 3:16; Heb 5:7), and the believer’s life in the body (Gal 2:20). As a part of man, it is sometimes used to represent the whole of him (Acts 2:17). Sarx is sometimes used to distinguish man’s material body from his immaterial self. When Jesus evangelized Nicodemus, He emphasized the imperative of the new birth: “That which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is

12

spirit” (John 3:6). Christ further contrasted flesh and spirit in describing the nature of His redeeming work: “It is the Spirit who gives life; the flesh profits nothing. The words that I speak to you are spirit, and they are life” (John 6:63).

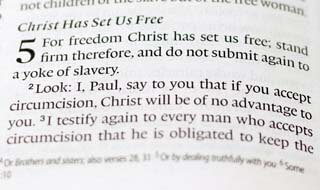

The New Testament further specifies the natural state of those unregenerated as “in the flesh” (Rom 7:5), who characteristically “walk after the flesh” (2 Pet 2:10). Those who are redeemed by Christ are not exempt from the ongoing effects of the flesh as a negative influence. The ethical use of sarx is typically evil, indicating selfish autonomy instead of godliness. Paul uses sarx this way in Rom 7:18: “For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh) nothing good dwells . . . .”

Terms Used for the Soul

The Hebrew term for soul is nephesh, occurring about 750 times in the Old Testament. The root idea of nephesh and related cognate words in Akkadian and Ugaritic is “throat,” or “breath.” Brown, Driver, and Briggs’ lexicon classifies ten shades of meaning for this word, including “soul,” “life,” “creature,” “person,” and “mind.” [13] Nephesh identifies that which breathes. It can be distinct from the body (Isa 10:8), yet is closely associ-ated with it (Job 14:23). Nephesh leaves the man’s body

13

at death, and if it returns supernaturally, the body’s life is restored (1 Kgs 17:21; Gen 35:18).

Living creatures exist due to the creative acts of God. Animals were created and designated as having nephesh (Gen 2:19,30). (Man’s creation was distinct from animals by virtue of his higher status; he was made in the image of God–Gen 1:26; 2:7.) Life is identified with a creature’s blood; this forms the basis of the value of substitutionary sacrifice of animals. In Lev 17:11 God states,

“For the life [nephesh] of the flesh is in the blood, and I have given it to you upon the altar to make atonement for your souls [nephesh]; for it is the blood that makes atonement for the soul [nephesh].”

The latter two occurrences (“your soul”) seem to point to the person’s spiritual life. However, in the first occur-rence, nephesh refers to “vitality, the passionate existence of an individual.” [14]

Since nephesh conveys the idea of individual life, it can stand for the man himself (without distinguishing his immaterial side). It identifies people in the poetic literature (Ps 25:12), as well as the historical literature (Num 30:14). It is used in numbering people (Josh 10:28), and can refer to individuals or groups (Deut 4:9: Is 46:2). By a peculiar figure of speech, nephesh is used of dead bodies in Num 5:2; 6:6. How can the noun indicating “breath” be used of a body not breathing? Waltke explains

14

that when nephesh is applied to a dead person, it is used to emphasize their identity as persons who have died, not to equate nephesh with the body. [15]

The other uses of the term cover areas related to man’s appetites, will, emotions and thoughts. Nephesh can indicate man’s appetites such as hunger (Deut 23:24), thirst (Ps 107:9), and the sexual drive (Jer 2:24). Man’s soul can express volition toward an enemy (Ex 15:9), or extending political rule (2 Sam 3:21). The soul’s capacity to love is mentioned in the Cant 1:7; 3:1-4. Nephesh can extend love in friendship (1 Sam 20:17), or its opposite–hatred (2 Sam 5:8). The soul can express a variety of emotions, such as joy or sorrow (Ps 86:4; Job 27:2) and personal thoughts (Prov 23:17).

Rarely, nephesh is used of God. This differs from the usual meanings and should be understood in a figurative sense because “God does not have the cravings and appetites common to man nor is his life limited by death.” [16] God rebuked Judah, ” ‘Shall I not punish them for these things?’ says the LORD. ‘And shall I not avenge Myself [my nephesh] on such a nation as this?'” (Jer 5:9). This example shows the reason for the use of nephesh. In this context the connotation of hard breathing expresses the intensity of God’s holy zeal.

15

Since it conveys the idea of breathing, nephesh is usually associated with the physical nature of man. However, this emphasis in Hebrew thought must not ignore the texts cited above which indicate that the soul is distinct and separable from the body. This distinctive aspect of soul becomes more pronounced in the equivalent term in the New Testament, psuche.

This word for soul occurs about 100 times in the New Testament. It is derived from the verb psucho, “to breathe.” Psuche occurs about 600 times in the LXX as the translation of nephesh. Cremer’s lexicon gives its basic meaning:

“In universal usage, from Homer downwards, psuche signifies life in the distinctiveness of individual existence, especially of man, and occasionally, but only ex analogia, of brutes. . . As to the use of the word in Scripture, first in the O.T. it corresponds with nephesh, primarily likewise — life, breath, the life which exists in every living thing, therefore life in distinct individuality.” [17]

In classical Greek, psuche originally had an impersonal connotation; thumos was more apt to refer to the conscious soul. Eventually the meaning of psuche broadened to include both life and consciousness, which is expressed in the Koine Greek of the New Testament. [18]

16

The basic usage of psuche conveys the idea of “the vital force which animates the body and shows itself in breathing.” [19] It is used in that sense regarding people (Acts 20:10) and animals (Rev 8:9). This natural life of the body is used to affirm the humanity Christ (Matt 2:20). In His ministry Jesus counseled, “Therefore I say to you, do not worry about your life [psuche], what you will eat; nor about the body, what you will put on” (Luke 12:22). In sacrificial love, Jesus laid down his life [psuche] for His sheep (John 10:11). Since the soul animates the body, these two aspects of man are interrelated. By synecdoche, soul can be used to denote the person or organism which has life (1 Cor 15:45); “every soul” can mean “every one” (Acts 2:43; 3:23). Likewise, in enumeration, people can be identified as “souls” (Acts 2:41).

Another meaning of psuche is to denote man’s inner self. The inner functions of soul include emotions such as sorrow (Matt 26:38), discouragement (Heb 12:3), vexation (2 Pet 2:8), joy (Luke 1:46), zeal (Col 3:23), and love (Matt 22:37). The will and desire are also functions of the soul (Eph 6:6; Rev 18:14). These responses necessarily involve perception (Acts 3:23; Heb 4:12). These faculties describe the individual’s personality. “Psuche means the inner life of man, equivalent to the ego, person, or

17

personality, with the various powers of the soul.” [20] Paul and his co-workers lovingly imparted, as it were, their very souls to the Thessalonian church (1 Thes 2:8). Christ offered peace and rest of soul to those who come to Him (Matt 11:29).

An important issue for this study on the consti-tuent parts of man is the question: Is the psuche an immaterial, invisible part of man, or simply an aspect of the living, physical body? While not retaining the Greek idea of the innate immortality of the soul, the New Testament usage indicates it is a distinct and separable part of man: “And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. . .” (Matt 10:28). This soul is the “essence which differs from the body and is not dissolved at death.” [21] Salvation involves saving the soul unto eternal life (Heb 10:38; 1 Pet 1:3-9).

“Jas 1:21 and 5:20 speak of the salvation of the soul which is in danger. The death from which it is said that the soul will be saved is eternal death, exclusion from eternal life . . . The soul, is the part of us which believes and is sanctified is destined to an inheritance in God’s future kingdom.” [22]

This salvation requires purification by God’s grace (1 Pet 1:22). Spiritual life has greater value than mere physical life, for it continues after death (John 12:25; cf. Phil 1:23).

18

The soul is identified as a distinct part of man when it is contrasted to the physical part: “Beloved, I pray that you may prosper in all things and be in health, just as your soul prospers” (3 John 2). Although the concept of this separation of the soul from the body is found in Greek literature, the historian Josephus, and Philo of Alexandria, the biblical doctrine is based on exegesis of the text of the New Testament. [23] The intermediate state of the believer between death and resurrection involves the conscious soul:

“. . . I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the testimony which they held. And they cried with a loud voice, saying, “How long, O Lord, holy and true, until You judge and avenge our blood on those who dwell on the earth?” (Rev 6:9,10; cf. 20:4). [24]

Although this quotation comes from apocalyptic literature, the intermediate state is also evident in historical passages. On the Mount of Transfiguration Jesus spoke with Moses and Elijah after their physical death (Matt 17:3).

Terms Used for the Spirit

The word typically translated “spirit” in the Old Testament is ruach, which occurs about 380 times. Ruach is probably related to the root meaning “to breathe.” Its basic meanings include “wind,” “breath,” “mind,” and “spirit.” It is the noun of the Hebrew verb riah, meaning

19

“to smell,” “accept.” In its concrete usage, ruach signifies the breath of living creatures (Job 15:50; 16:3), and is so used of people as well as animals (Isa 42:5; Ps 104:25,29).

As hard breathing in the nostrils it is used figura-tively to denote emotions such as anger in man or (poetically) in God (Isa 25:4; Ex 15:8). This kind of quick breathing can convey various other dispositions of the inner self: vigor (1 Sam 30:12), courage (Josh 5:1), impatience (Micah 2:7), bitterness (Is 54:6), jealousy (Hos 4:12), and motivation (Ezra 1:1,5). When the Queen of Sheba was overwhelmed by Solomon’s attainments, she had no more ruach, i.e. was “breathless” (1 Kgs 10:5). A person’s ruach may be contrite (Isa 57:15), or sad (1 Kgs 21:5). Spirit can likewise refer to one’s character such as being wise (Deut 34:9), unfaithful (Hos 4:12), proud (Eccl 7:8), or jealous (Num 5:14).

In its use as atmospheric wind, ruach describes storm winds (Isa 25:4), directional winds, the four winds (Ex 10:13; Prov 25:23; Jer 49:36), or wind from heaven (Gen 8:1). Metaphorically, ruach can mean something vain or empty: “Remember that my life is a breath [ruach]! My eye will never again see good” (Job 7:7). This derivation of wind makes ruach more abstract from man than the basic ides of nephesh (which was originally associated with the throat).

One of the main uses of this word is to describe God. J. Barton Payne summarizes Old Testament references

20

to the activity of the Spirit of God:

“The work of God’s Spirit may be cosmic, whether in creation (Job 26:13) or in continuing providence (Job 33:4; Ps 104:30); redemptive, in regeneration (Ezek 11:19; 36:26,27); indwelling, to uphold and guide the believer (Neh 9:20; Ps 143:10; Hag 2:5); or infilling, for leadership (Num 11:25; Jud 6:34; 1 Sam 16:13), service (Num 11:17; Mic 3:8; Zech 7:12), or future empowering of the Messiah (Is 11:2; 42:1; 61:1), and his people (Joel 2:28; Is 32:15). “[25]

These activities and attributes point to God’s Spirit being more than an impersonal influence; He is a person. This doctrine of the Holy Spirit as a co-equal, distinct person of the Godhead is made explicit in the New Testament. Since the same Hebrew word for spirit is used in referring to God and man, the context is important in determining the exact usage. The same commonality occurs in the New Testa-ment’s use of pneuma. Angels are other personal spiritual beings identified by ruach (1 Sam 16:23; Zech 1:9).

Although liberal scholars interpret ruach as an impersonal life-principle which cannot exist apart from the body, the Old Testament data supports the essential dualism of man as having distinct material and immaterial parts. Eccl 12:7 describes the outcome of man’s physical death: “Then the dust will return to the earth as it was, And the spirit [ruach] will return to God who gave it.” Both nephesh and ruach are said to leave the body at death and exist separately from it (Gen 35:18; Ps 86:13). The Hebrew emphasis on wholeness does not negate these observations.

21

This term pneuma is the New Testament equivalent of ruach. Occurring over 350 times, its essential definition is “wind,” or “spirit.” The root pneu has the idea of the dynamic movement of air. The related words convey the ideas of blowing (of the wind, or playing a musical instrument), breathing, emitting a fragrance, giving off heat, etc. [26] The verb form is always used of blowing wind in the New Testament (Matt 7:25,2), unless John 3:8 is interpreted as referring to the Holy Spirit’s activity.

Although the noun pneuma can retain the literal idea of wind (Heb 1:7), it usually refers to spiritual beings, entities, or qualities. As the Old Testament usage of nephesh and ruach overlap, so also does the use of psuche and pneuma. F. Foulkes observed, “Many things can be said to describe the action of man’s spirit as his functioning in his essential being.” [27] In an abstract sense, pneuma can refer to one’s purpose (2 Cor 12:18; Phil 1:27) or character (Luke 1:17; Rom 1:4). Moral qualities are spoken of in terms of spirit. Bad qualities include a spirit of bondage (Rom 8:15), stupor (Rom 11:8), or timidity (2 Tim 1:7); good qualities of spirit include faith (2 Cor 4:13), meekness (1 Cor 4:21), liberty (Rom 8:15), and quietness (1 Pet 3:4). Contextual clues are needed to determine when spirit is used in an abstract way.

22

Pneuma frequently refers to noncorporeal beings such as angels. Good angels are identified in passages such as Heb 1:14: “Are they not all ministering spirits sent forth to minister for those who will inherit salvation?” Bad angels are called unclean or evil spirits. Forty times the New Testament mentions this class of fallen angels as “spirits” (e.g. Matt 8:16; Luke 4:33). Since the spirit of man can be influenced by good or evil spiritual beings, believers are summoned to exercise discernment: “Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits, whether they are of God. . . ” (1 John 4:1). This conflict of good versus evil should not be construed as teaching dualism. As Brown notes,

“But at no time do the NT writers give way to dualism, where the evil which thus manifests itself is as strong as God. Always the evil spirits are shown inferior to God and subject to the power of the Spirit of God operating through his agents. ” [28] Thus, God’s sovereignty is not compromised.

Pneuma is also used of the third person of the triune God, who is coequal and co-eternal with the Father and the Son. He is designated by pneuma about 90 times in the New Testament. Sometimes the definite article is used which is common when the context emphasizes His persona-lity, or His distinction from the Father and the Son (Matt 12:31,32; John 14:26; 15:26). [29] In some contexts the

23

distinction between man’s spirit and the Holy Spirit is ambiguous. For example, Rom 8:4,5 states:

“That the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us who do not walk according to the flesh but according to the Spirit [or spirit]. For those who live according to the flesh set their minds on the things of the flesh, but those who live according to the Spirit [or spirit], the things of the Spirit.”

The regenerating work of the Spirit of God in the believer makes man’s spirit alive, but He does not take the place of it. As Cremer’s lexicon observed:

“Always according to the context, we must understand by pneuma the divine life-principle by nature peculiar to man, either in its natural position within his organism, or as renewed by the communication of the Spirit . . . But we must hold fast the truth, that this newly given life-principle [the Spirit in His regenerating work–Rom 8:9] does not become identical with the spirit belonging to man by nature, nor does it supplant it.” [30]

Pneuma refers to a part of man’s makeup about forty times. This does not endorse the Greek model of trichotomy which equates spirit with reason and views matter as evil.

“The NT writers can speak of the human spirit as though it was a something possessed by the individual; but this does not mean they envisaged the spirit of man as a divine spark (the real ‘I’) incarcerated in the physical . . . . “[31]

The pneuma in man is not a universal spirit or perfected soul. When contrasted with flesh, pneuma refers to man’s immaterial part (2 Cor 7:1). Like the soul, it can refer to man as separate from his physical body; thus Heb 12:23

24

can speak of the scene of God’s presence including “the spirits of just men made perfect” (cf. Luke 24:37,39)

The usage of pneuma often overlaps that of psuche but some passages indicate that they are more than synonyms for the immaterial part of man. An analysis of their New Testament usage shows distinctive connotations for each of them. [32] In 1 Thes 5:22,23 and Heb 4:12, they do not merely refer to different functions or roles; they are identified as distinct parts of man.

The use of the adjective pneumatikos and adverb pneumatikoos further substantiate the distinction between soul and spirit. Thayer gives one of the definitions of the adjective pneumatikos “as the part of man which is akin to God and serves as his instrument or organ” (cf. 1 Cor 15:44,46). [33] The adverb pneumatikoos seems to allude to the pneuma as a distinct part of man in 1 Cor 2:14:

“But the natural man does not receive the things of the Spirit of God, for they are foolishness to him; nor can he know them, because they are spiritually [relating to the spirit] discerned.”

A related New Testament term for spirit is “heart.” Its equivalent Greek word, kardia, occurs almost 150 times in the New Testament. The Old Testament used leb for heart, which was usually translated as kardia in the LXX. The Hebrew use of heart was either physical (Gen 18:5; Jud 19:5) or metaphorical. The latter use is the common

25

one, which viewed the heart as the seat of man’s spiritual and intellectual life. This involved the emotions (Deut 28:47), the mind (1 Kgs 3:12; 4:29), and the will (Ex 36:2). Leb is:

“a comprehensive term for the personality as a whole, its inner life, its character. It is the conscious and deliberate spiritual activity of the self-contained human ego and the seat of his responsibility.” [34]

The use of kardia in the New Testament is consistent with leb. It rarely refers to the physical heart (Luke 21:34), but characteristically describes the inner life of man (2 Cor 5:12). This use of kardia can represent the whole inner life (1 Pet 3:4), the psycho-logical part of man (2 Cor 4:6; 9:7; Eph 6:22), or his spiritual orientation (Matt 22:37). The sinful heart is deceitful (Mark 7:6), enslaved (Mark 7:21), and corrupt (Rom 1:24). Through salvation in Christ the heart is opened to God’s grace (Acts 16:4), illumined by His truth (2 Cor 4:6), and enriched by His love (Rom 5:5). There is not adequate biblical evidence for identifying heart as a constituent part of man, distinct from soul and spirit.

Other related terms in the New Testament express different aspects of man’s inner life. The “mind” is translated from phronema or the more commonly in its verbal form (Acts 28:22;Rom 12:3). The “will” is translated from the verbs thelo (Matt 1:198:2), or bouomai (Luke 10:22; John 18:39); and emotions are described by a variety of nouns and verbs. The spiritual function of conscience is

26

denoted by suneidesis (Acts 23:1). Inductive study leads to the conclusuon that such terms identify various func-tional attributes of the soul and spirit

Summary

The word studies in this chapter have traced the meaning and usage of the basic terms in the Bible that relate to man’s makeup. This data shows many ways that soul and spirit are used interchangeably, especially in the Old Testament. Some distinctions in New Testament usage between soul and spirit have been noted and more will be identified in subsequent chapters. Milton Terry warned against coming to a conclusion about the doctrine of man’s makeup based only on “the rhetorical language of biblical writers who follow no uniform usage of the same words”. [35] However, he and other dichotomists uniformly agree spirit has a higher connotation than soul in biblical literature. While it is conceded that word studies alone are not conclusive for this doctrinal issue, biblical exposition gives adequate evidence to support the distinction of soul and spirit as being more than merely one of emphasis. This issue is relevant because a precise theological model of man’s constituent parts and their faculties is integral to one’s view of sanctification, psychology, and counseling. The next chapter will survey the three prominent theolo-gical positions regarding the makeup of the human being.

Footnotes

9 Anthony A. Hoekema, Created in God’s Image (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1986), 203.

10 James Orr, ed., The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, s.v. “Psychology,” by J. I. Marais, 4: 2495.

11 William Barclay, More New Testament Words (New York: Harper, 1958), p.9, quoted in Cyril J. Barber, Introduction to Theological Research (Chicago: Moody Press, 1982), 111.

12 J.D. Douglas, New Bible Dictionary (Wheaton: Tyndale House, 1962), s.v. “Body,” by B. O. Banwell, 145.

13 F. Brown, S. R. Driver, and C. A. Briggs ed., Hebrew and English Lexicon to the Old Testament (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957), s.v. “Nephesh,” 659.

14 Laird Harris, Gleason Archer, and Bruce Waltke eds., The Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament [TWBOT], s.v. “Nephesh,” by Bruce Waltke, 2:590.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid., 591

17 Herman Cremer, Biblical-Theological Lexicon of the New Testament Greek, [BTLNTG]trans. William Urwick (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1895), s.v. “Psuche,” 592,93.

18 Colin Brown ed., The New Internaional Dictionary of New Testament Theology [NIDNTT] (Exeter: Paternoster Press, 1975), s.v. “Soul,” 3: 677.

19 Joseph H.Thayer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament [GELNT] (Grand Rapids: Baker book House, 1977), s.v. “Psuche,” 677.

20 Brown, NIDNTT, 3: 683.

21 Thayer, GELNT, 677.

22 Brown, NIDNTT, 3: 685.

23 Brown, IDNTT, 3: 681.

24 Any words highlighted in biblical quotations are for added emphasis by this writer.

25 J. Barton Payne, TWBOT, 2:837.

26 Brown, NIDNTT, 3: 689.

27 M. Tenney ed., The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible [ZPEB], s.v. “Spirit” by F. Foulkes, 5: 505.

28 Brown, NIDNTT, 695.

29 W. E. Vine, Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words (Westood, NJ: Flemming H. Revell, 1940), 63.

30 Cremer, BTLNTG, 506.

31 Brown, NIDNTT, 3: 694.

32 R. W. F. Wooton, “Spirit and Soul in the New Testament,” The Bible Translator. 26 (1975) 239-44.

33 Thayer, GELNT, 523.

34 Brown, NIDNTT, 2:181

35 Milton S. Terry, Biblical Dogmatics: An Exposition of the Principal Doctrines of the Holy Scriptures (NY: Eaton and Mains, 1907), 53.

copyright , John Woodward, 2000