THEOLOGICAL MODELS OF MAN’S MAKEUP

Monism

Monism is the theological model that considers man as having only one part. Although soul and spirit are identified as aspects of human nature, they do not consist in separable parts of man. Monism opposes both dichotomy and trichotomy, the usual evangelical models of man. As Philip Hefner contends,

“Contemporary understanding of the human being and the human personality structure do not allow either a dichotomous or a trichotomous view, except metaphorically.” [1]

In his discussion of the models of man’s constitutional nature, Millard Erickson (as a dichotomist) writes:

“Monism insists that man is not to be thought of in any sense composed of parts or separate entities, but rather as a radical unity. In the monistic understanding, the Bible does not view man as body, soul, and spirit, but simply as a self. The terms sometimes used to distinguish parts of man are actually to be taken as basically synonymous. Man is never treated in the Bible as a dualistic being.” [2].

Monism has been the trend in academic circles in this century. Liberal theologians as well as neo-orthodox scholars have been advocating it. Wayne Ward summarized this trend by stating,

28

“Present theological and psychological emphasis is almost altogether upon the fundamental wholeness or unity of man’s being. . . “[3] This monistic perspective is also held by some evangelical scholars:

“Today the dichotomy/trichotomy issue has been largely superseded by an emphasis on the unity of the person. According to Scripture I do not consist of composite ‘parts,’ whether two or three; I am a psycho-somatic unity.” [4]

Likewise, Anthony Hoekema avoids the use of the terms “dichotomy” or “trichotomy” because they deemphasize man’s essential unity.

” . . . We must reject the term “dichotomy” as such, since it is not an accurate description of the biblical view of man. The word itself is objectionable. . . It therefore suggests that the human person can be cut into two “parts.” But man in this present life cannot be so cut. . . The Bible describes the human person as a totality, a whole, a unitary being.”5

Both Milne and Hoekema concede that man’s immaterial part separates at the time of physical death, thus they actually hold to a form of dichotomy. Physical monism, however, requires the belief that the soul does not survive the death of the body. Some theologians reconcile this in their eschatology, teaching that the soul and body are recreated by God ex nihilo at the resurrection. This view is known as recreationism.

29

Some theologians advocate spiritual monism. Instead of seeing the body and soul as an individual physical monad, these see man as an indivisible spiritual monad. Thus, the body is regarded as an illusion, as maya in Hinduism. The strong influence of eastern religions in the west has found “Christian” counterparts: e.g. Christian Science, Process Theology, and Gnosticism. [6]

Roman Catholic tradition also supports a monistic view of man. Thomas Aquinas advocated a middle position between the dualism of Plato and the monism view of Aristotle (who compared the body with lumber and the soul with an architectural plan). However, Aquinas did write that “man is composed of a spiritual and of a corporeal substance,” and that the soul survives death.”[7] But Catholic anthropology in this century regards the survival of the soul after physical death as a mystery; man is regarded as an ontological unity.

“The unity of the soul and body is so profound that one has to consider the soul to be the ‘form’ of the body; i.e. it is because of the spiritual soul that the body of matter becomes a living, human body; spirit and matter in man, are not two natures united, but rather their union forms a single nature.” [8]

Monism is sometimes advocated on scientific grounds. Calvin Seerveld urges evangelicals to discard the outdated belief in body, soul, and spirit as parts of man’s constitution.

30

He bases man’s identity on “the structured thrust of the whole,” which he considers indivisible.[9] Yet this bias against the distinctive soul of man seems due to its immaterial quality. As George Jennings noted, this contemporary preference by social scientists, anthropologists, and psychologists to abandon the concept of the soul is due to their inability to study the soul experimentally.[10] Boyd described the trend in the Evangelical Theological Society as using “spirit” as a replacement for the term “soul,” with a monistic emphasis on man’s nature. He concluded that many theologians confess that they have not thought enough about the soul, therefore theological anthropology is an underdeveloped and neglected aspect of evangelical theology.[11]

A prominent example of a case for monism is The Body , by John A. T. Robinson. A representative of the biblical theology movement, this neo-orthodox scholar assumed a sharp distinction between Greek and Hebrew thought. He agreed with H. Wheeler Robinson’s assessment of the Hebrew idea of personality–man as an animated body, not an incarnated soul. So Robinson affirmed, “Man is a unity, and this unity is the body as a complex of parts, drawing their life and activity from a breath soul, which has no existence apart from the body.”[12] In his work on

31

systematic theology,Erickson identifies major arguments for monism and answers them effectively.

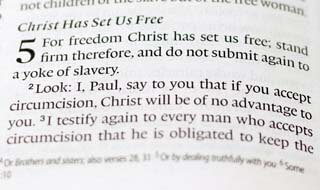

Without going into further detail in responding to monism, it should suffice to examine biblical passages which refute this position. A basic testimony against monism is the indication that man’s soul continues to live after the body dies; this necessitates the doctrine of the soul as an element distinct from the physical body. The Old Testament refers to this when Rachel’s soul departed (Gen 35:18), and Ecclesiastes speaks of man’s spirit as returning to God after death (Eccl 3:21). In the New Testament, Christ promised the thief on the cross that they would be in Paradise that very day (Luke 23:43). This would sharply contrast the condition and location of their crucified bodies. The apostle Paul testified:

“For I am hard pressed between the two [whether to prefer longer physical life or martyrdom] having a desire to depart and be with Christ, which is far better. Nevertheless to remain in the flesh is more needful for you” (Phil 1:23,24; cf. 2 Cor 5:8; Heb 12:23; Rev 6:9).

Other references also indicate the distinction between soul and body. Daniel testified that his spirit was grieved in the midst of his body (Dan 7:15). Jesus warned His disciples not to fear human persecutors: “And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. . . ” (Matt 10:28). I. Howard Marshall confesses that most current biblical scholars are embarrassed by the dualism in Matt 10:28, preferring to minimize it.[13] Nevertheless, here a clear distinction is drawn between man’s material and immaterial parts. Delitzsch refuted monism when he wrote:

32

“If. . . the conclusion be drawn that there subsists no essential distinction between soul and body, Scripture is diametrically opposed to this; for it bids us from the first page to look upon the kosmos dualistically, so also it bids us look at man. . . for the spirit. . . is something essentially different in its nature from matter. According to its representation, man is the synthesis of two absolutely distinct elements.”[14]

These observations show that, although the Scriptures value man’s unity of personhood, there is an undeniable distinction of parts in his being (3 John 2). Further refutations of monism come from some of the biblical arguments for dichotomy.

Dichotomy

This view of human nature sees man’s constituent elements as two–the physical and the spiritual. The term “dichotomy” derives two Greek roots: diche, meaning “twofold” or “into two”; and temnein, meaning “to cut.” Strong states this view:

“Man has a two-fold nature,–on the one hand material, on the other immaterial. He consists of body, and of spirit, or soul. That there are two, and only two, elements in man’s being, is a fact to which consciousness testifies. This testimony is confirmed by Scripture, in which the prevailing representation of man’s being is that of dichotomy.”[15 ]

Just As there are two varieties of monism (physical and spiritual), there are two varieties of dualism (Platonic and holistic). Plato’s teaching is representative of Greek dualism.

“Plato saw man as two separable parts, body and soul; at death the soul was liberated, the divine spark in man passing from its shadowy life in the prison-house of the body to the real world beyond physical dissolution.”[16]

33

Thus, Greek philosophers regarded the body as intrinsically bad, in contrast to the soul. (This negative attitude toward the body is seen in the criticism of the doctrine of the resurrection by the philosophers of the Areopagus in Acts 17:32). Descartes’s form of dualism likewise emphasized the separate substances of body and soul.

Holistic dualism maintains the distinction in man’s constitution while emphasizing his unity. This view goes by a variety of titles such as “minimal dualism” (C. S. Evans), “interactive dualism” (Gordon Lewis), “conditional unity” (Millard Erickson), or “psychosomatic unity” (Anthony Hoekema). Lewis and Demarest advocate this position:

“To sum up the doctrine of humanness ontologically,. . . the whole person is a complex unity composed of two distinct entities, soul and body, intimately interacting with one another. . . an interacting dichotomy.”[17]

How does this view of dualism differ from that of Plato? Lewis and Demarest further clarify that,

“The body is not the blameworthy cause of human evil, the inner self is. The existence of the naked spirit after death is an intermediate and incomplete state, not the eternal state. In the eternal state humans are not immortal souls only, but spirits united with resurrection bodies. . . [The body] is not the prison house of the soul but its instrument. The body is not less real than the soul.”[18]

If Platonism viewed the body and soul as joined in a bad marriage, holistic dualism sees them as in a harmonious one.

Scriptural support for dichotomy was arranged by Strong in four observations. First he noted

34

The record of man’s creation (Gen 2:7), in which, as a result of the inbreathing of the divine Spirit, [indicates that] the body becomes possessed and vitalized by a single principle–the living soul.[19]

Secondly, Strong observed texts in which the soul (or spirit) is distinguished, both from the divine Spirit–from whom it pro-ceeded–and from the body which it inhabits (Num 16:22; 12:1; 1 Cor 2:11). Various texts distinguish the soul, or spirit of man from the body (1 Kgs 17:21; Gen 35:18; James 2:26).

Thirdly, Strong noted the interchangeable use of the terms “soul” and “spirit”: they both are used to refer to emotions (Gen 41:8; Psalm 42:6), Jesus giving of his life (Matt 20:28; 27:50), and the intermediate state of man (Heb 12:23; Rev 6:9). Fourthly, Strong pointed to the mention of body and soul (or spirit) as together constituting the whole person (3 John 2; 1 Cor 5:3; Matt 10:28).20

Berkhof gives an historical survey of this doctrinal view and then endorses dichotomy. He first notes the biblical emphasis on the unity of man’s person:

“While recognizing the complex nature of man, it [the Bible] never represents this as resulting in a twofold subject in man. Every act of man is seen as an act of the whole man. It is not the soul but man that sins; it is not the body but man that dies; and it is not merely the soul, but man, body and soul, that is redeemed by Christ.”[21]

He then proceeded to explore the nature of man’s duality. Occasionalism (suggested by Cartesius) is rejected because it

35

proposes that matter and spirit each function according to their own peculiar laws; these laws are so different that joint action of soul and body are impossible without divine intervention. Another theory of the relationship of soul and body is paralle-lism (proposed by Leibnitz). This view also assumes that there is no direct interaction between the material and spiritual, yet God is not the source of the apparent harmony of the two in man’s activity. Instead, there is a pre-established harmony so that they act in concert with each other; when the body moves, the soul has a corresponding movement. Berkhof affirms the majority view of dichotomy which he calls “realistic dualism”: “. . . body and soul are distinct substances which do interact, though their mode of interaction escapes human scrutiny and remains a mystery for us.”[22]

To substantiate dichotomy over trichotomy, the soul and spirit are defined as denoting the same immaterial part of man, yet with distinct connotations. Dichotomist theologians have different ways of clarifying this distinction. Gordon Clark is representative of those which identify “soul” as the combination of body and spirit. Commenting on Geneses 2:7 he writes,

” . . . God constructed man out of two elements: the dust of the ground and his own breath, The combination is nephesh. . . In the Old Testament the term “soul” designates the combination as a whole, not just one of the components.”[23 ]

Strong defines “soul” as “the immaterial part of man, viewed as an individual and conscious life, capable of possessing and

36

animating a physical organism.” “Spirit” is then described as this same immaterial part “viewed as a rational and moral agent, susceptible of divine influence and indwelling.”[24] He continues these contrasts:

“The pneuma, then, is man’s nature looking Godward, and capable of recieving and manifesting the pneuma hagion; the psuche is man’s nature looking earthward, and touching the world of sense . . . [man’s] immaterial part, while possessing duality of powers, has unity of substance.”[25]

This perspective is echoed by dichotomists, as in this summary by J. O. Buswell:

“As “soul” designates the non-material personal being, usually when there is some reference to his body or his earthly connections. . . so the word “spirit” designates a personal being in those circumstances in which reference to earthly connections and ordinary human function is absent.”[26 ]

The understanding of spirit as the higher aspect of man’s immaterial being is a consistent feature of dichotomist theologians; they reject, however, the ontological distinction between soul and spirit.

Trichotomy

A definition of trichotomy is given by Paul Enns:

“Trichotomy comes fro the Greek tricha , “three,” and temno , “to cut.” Hence, man is a three part being, consisting of body, soul, and spirit. The soul and spirit are said to be different both in function and substance.”[27 ]

37

The distinction of soul and spirit, however, does not require an emphasis on disunity of the human constitution. As recent dichotomists emphasize the unity of man’s nature, so the tricho-tomist can value this unity. J. B. Heard reflected this balance in his definitive work, The Tripartite Nature of Man :

“We may distinguish in idea, as we shall presently see Scripture does, between body, soul, and spirit; but to suppose that either can act without the other, or to suppose, for instance, that the unsouled body, or the disembodied soul, or lastly, the unsouled spirit, can act by itself, is to assume something which neither reason nor revelation warrants. . . The facts of consciousness are all against such a trichotomy as would divide as well as distinguish the natures in man.”[28]

Thus, the perception of three parts of man’s makeup does not require a neglect of emphasis on man’s unity of personhood. Likewise, trichotomy agrees with most of the biblical propositions of dichotomist theologians. L. T. Holdcroft acknowledges this common ground as he defines trichotomy:

“The trichotomist divides the non-material element of the human into two parts, so that with the body, he views humans as three-part or tripartite beings. In the traditional language, the trichotomist usually speaks of: body, soul and spirit. In most cases, the trichotomist freely accepts the dichotomist’s Scriptures [interpretations] and probably most of his arguments. The two viewpoints agree that man is both material and non-material, and therefore the trichotomist does not so much object to what has been done [by dichotomists], but rather simply seeks to proceed a step further.”[29 ]

Articulations of Trichotomy

It has been noted that recent scholarship favors a monistic view of man, although evangelical scholarship is

38

usually dichotomist. Trichotomy has, nevertheless, been popular among more fundamental Bible teachers since its resurgence in the previous century. One example of this view is the following note from the Scofield Reference Bible. Commenting on 1 Thes 5:13 it states,

“Man is a trinity. That the human soul and spirit are not identical is proved by the facts that they are divisible (Heb 4:12), and that the soul and spirit are sharply distinguished in the burial and resurrection of the body . . . (1 Cor 15:44).”[30 ]

G. H. Pember wrote of the distinctive functions of man’s three parts:

“Now the body we may term the sense-consciousness, the soul the self-consciousness, and the spirit the God-consciousness. For the body gives us the five senses; the soul comprises the intellect which aids us in the present state of existence, and the emotions which proceed from the senses; while the spirit is our noblest part, which came directly from God, and by which alone we are able to apprehend and worship Him.”[31]

Some have postulated that the spirit of man is that part of him which distinguishes him from animals (not just quali-tatively, but substantively). Defining the soul, the author of Biblical Doctrine wrote,

“The soul is the seat of the emotions and appetites. Plants, animals and man have bodies. Only animals and man have a soul; but only man has a spirit. . . There is a difference between the souls of man and the souls of animals. . . The soul of an animal dies with the animal, but man’s soul never dies. . . The spirit of man is the seat of his intelligence (1 Cor 2:11). Animals do not possess intelligence.”[32]

39

The view that animals do not possess a spirit, however, is not a necessary tenant of trichotomy. The Hebrew word ruach is used of animals in Gen 7:15 and Ps 104:15,29 (although, ruach may be interpreted in those contexts in the physical sense of “breath”). Most trichotomists would agree with the majority view–that man and animals alike have “spirit,” but man’s spirit is qualitatively higher due to his dignity as made in God’s image.

Some theologians who hold to a trichotomist view are not dogmatic; they state that the Scriptures can be interpreted to support both trichotomy and dichotomy. L. S. Chafer states this in his Systematic Theology:

” . . . The Bible supports both dichotomy and trichotomy. The distinction between soul and spirit is as incomprehensible as life itself, and the efforts of men to frame definitions must always be unsatisfactory. . .”[33]

When it appears that Chafer will be non-committal, he goes on to note,

“. . . many have assumed that the Bible teaches only a dichotomy. Over against this is the truth that oftentimes these terms cannot be used interchangeably. At this point it may be observed that there is the closest relation between the human spirit and the Holy Spirit–so close, indeed, that it is not always certain to which a referenceis made in the sacred text. . . The Holy Spirit works in and through the human spirit, but this is not said of the human soul. “The Spirit itself beareth witness with our spirit.” (Rom 8:16). A soul may be lost, but this is not declared of the spirit (Matt 16:26).”[34]

Henry Theissen favored trichotomy but his definitions are not

40

strongly antithetical to dichotomy. He summarized,

“In other words, man’s immaterial nature is looked upon as one nature, but composed of two parts. Sometimes the parts are sharply distinguished; at other times, by metonymy, they are used for the whole [immaterial] being.”[35]

Man’s Constituent Parts

The Spirit

The dichotomist can concede that man’s spirit is distinct as a faculty or function of the soul, but trichotomy affirms a more pronounced distinction. One of the most influential, scholarly cases for trichotomy was that of Franz Delitzsch in his A System of Biblical Psychology . Dichotomists have taken note of his departure from the usual dichotomist view of evangelical scholars. They take various approaches to pay tribute to his work while maintaining a dichotomist view. For example, Buswell quoted Delitzsch, then interpreted his view:

“It should be evident to the reader that in this quotation [from Delitzsch] the word “distinct” [soul from spirit] means functionally distinct and not substantively distinct, a distinction of “aspect,” not of substance. There is nothing in Delitzsch’s work to show that the difference between “soul” and “spirit” is other than a difference of functional names for the same substantive entity, the same kind of difference that obtains between “heart” and “mind.”[36]

It is understandable why Buswell would try to interpret Delitzsch this way. To do so, however, Buswell takes selective quotes where Delitzsch is contrasting man’s material and immaterial elements. Such an interpretation of Delitzsch, which

41

seeks to nullify this theologian’s influential case for trichotomy, requires closer scrutiny.

In his book, Delitzsch identified the usual view of interpreting soul and spirit as different functional attributes, yet insists that trichotomy affirms a substantive difference:

“The psuche must be more than the form of existence, the individualization of of the spirit; for Scripture certainly appropriates to the spirit and soul different functions, and often in juxtaposition. They must be distinguished even otherwise [more than by mere function]. . . A man would then not be able to speak of his spirit specially, and of his soul specially.”[37]

He also rejected another approach to removing the substantive distinction between spirit and soul:

“Rather might spirit and soul be apprehended as only two distinct sides of one principle of life. . . But even this distinction is far from being sufficient for the case in question. . . The spirit is superior to the soul. The soul is its product, or, what is most expressive, its manifestation . . .”[38]

The chapter Buswell quotes from is titled “True and False Trichotomy.” Here Delitzsch interacted with various forms of both dichotomy and trichotomy, clearly advocating the latter.

“And as for the essential condition of man, I certainly agree entirely with the view that the spirit and soul of man are distinguished as primary and secondary, but not with the view that spirit and soul are substantially one and the same.”[39]

Whereas dichotomists require the possibility of soul and spirit separating (to prove their actual distinction), Delitzsch found validity in the concept of the potential separation of soul and spirit:

42

“If any one would rather say that the soul is a Tertium, or third existence, not substantially indeed, but potentially independent, between spirit and body, but by its nature pertaining to the side of the spirit, we have no objection to it.”[40 ]

His conclusions are softened by dichotomists because Delitzsch acknowledged the obvious; the distinction of the material and immaterial is more apparent and observable than the subtle distinctions between soul and spirit. He stated that soul and spirit are the same “nature.”[41] The difficulty of choosing accurate terms to express these delicate distinctions is evident. He looks to the relationship of the persons of the Trinity to parallel the distinction of man’s two immaterial parts:

“[The soul] is not one and the same substance with the spirit, but a substance which stands in a secondary relation with it. It is of one nature with it. . . as the Son and the Spirit are of one nature with the Father, but not the same hypostases.”[42]

In light of these representative quotes, Buswell’s attempt to reinterpret Delitzsch as dichotomist is invalid.

Heard published a thorough study of biblical psychology, defining and defending trichotomy. He also affirmed that the spirit is more than a function of the soul:

“The pneuma is, we admit, very closely joined to the psuche; but so is the psuche to the animal frame. If we can distinguish between soul and body, as all psychologists who are not materialists do; are we not bound equally to distinguish between soul and spirit? Consciousness is the common term which unites these three natures of man together. . . It is not, as dichotomists would say, that the

43

spirit is only the reasonable soul exercised upon the inner world of the spirit instead of the outer world of the sense.” [43 ]

C. A. Beckwith described the distinction of the human spirit as the divine principle of life in man; it is included in the soul, but distinct from it:

” . . . the spirit is the condition, soul the manifestation of life. Whatever belongs to the spirit belongs to the soul also, but not everything that belongs to the soul belongs to the spirit. . . it does not suffice to speak of the inner being of man, now as the spirit, now as the soul; one must regard the spirit as the principle of the soul, the divine principle of life, included in but not identical with the individual.”[44 ]

The human spirit is defined by Holdcroft as the animating principle which causes the man to be alive. God is the author of the human spirit (Num 27:16; Zech 12:1), and when the spirit is withdrawn, the body dies (Jas 2:26). The biblical references to the spirit of man in the New Testament are categorized by Holdcroft:

“1) those that identify strictly the human principle of life and 2) those that identify the expression of that life in feelings, convictions and motivations. In this second usage many see an overlap between the role of the spirit and that which is commonly identified as the human soul. At least it is clear that the human soul is more than merely an impersonal life principle; it is a human life-principle that is distinctive and individually personal.”[45 ]

Another example of this view that distinguishes spirit from soul is found in Oswald Chambers’ lectures on biblical

44

psychology: “The spirit is the essential foundation of man; the soul his peculiar essential form; the body his essential manifestation.”46 Expounding on the human spirit, he commented “Remember, the whole meaning of the soul is to express the spirit, and the struggle of the spirit is to get itself expressed in the soul.”[47] Yet the process of sanctification involves the whole person:

“God knows of no divorce whatsoever between the three aspects of the human nature, spirit, soul, and body; they must be at one, and they are at one either in damnation or in salvation.”[48]

Watchman Nee expressed the doctrine of trichotomy in a methodical, extensive way in his three volume The Spiritual Man. Speaking of the importance of identifying the spirit, he wrote:

“It is imperative that believers recognize a spirit exists within them, something extra to thought, knowledge, and imagination of the mind, something beyond affection, sensation and pleasure of the emotion, something additional to desire, decision and action of the will. This component is far more profound than these faculties. God’s people not only must know that they possess a spirit; they also must understand how this organ operates–its sensitivity, its work, its power, its laws. Only in this way can they walk according to their spirit and not the soul or body of their flesh.”[49 ]

Nee went on to identify and elaborate on three major faculties of man’s spirit–that of intuition, conscience, and communion.

45

The Soul

The soul is described by the data of the biblical word studies which bring out its distinctive functions. The Scofield Reference Bible defined the human soul as the “seat of the affections , desires , and so of the emotions , and of the active will , the self.”50 T. Austin-Sparks, an British pastor who assisted Watchman Nee (when Nee visited England), described the soul as:

“. . .the plane or organ of human life and communication . . . Thus, what is received by the spirit alone with its peculiar faculties is translated for practical purposes, firstly to the recipient himself, and then to other humans, by means of the soul. This may be an enlightened mind for truth (reason); a filled heart, with joy or love, etc., for comfort and uplift (emotion); or energized will for action or execution (volition).”[51]

Heard affirmed the soul’s faculty of free will:

“Soul, or self-consciousness as the union point between spirit and body, was created free to choose to which of these two opposite poles [the flesh or the spirit] it would be attracted …”[52]

Another representative of the Keswick movement, Jessie Penn Lewis, quoted Tertullian, Pember, and Andrew Murray in support of trichotomy. She summarized the functions of the soul:

“We see that all these writers practically define the “soul” as the seat of the personality, consisting of the will and the intellect or mind; a personal entity standing between the “spirit” and the “body”–open to the outer world of

46

nature and sense; the soul having power of choice as to which world shall dominate the entire man.”[53]

(Penn-Lewis’ writing preceded Watchman Nee’s which elaborated on these themes primarily for the believers in China.)

Some trichotomists identify the soul as the phenomenon of the union of man’s body and spirit. K. Liu wrote,

“The soul is the totality of the being, while the spirit is the immaterial vitality of the soul. The soul lives so long as the body is in contact with the spirit. The soul dies and is thus temporal while the spirit is never said to die and hence it must be immortal.”[54]

This view is based primarily on the exegesis of Gen 2:7 which describes the creation of man. However, this position encounters difficulty reconciling texts which describe the soul of man existing after death, but prior to the resurrection (Rev 6:9; 20:4; Matt 10:28)–although some have postulated that man is given an intermediate body (Matt 17:3; Luke 16:24).

The faculty of man’s affections seems equally applied to the soul and the spirit. This combination seems to correspond to the Biblical usage of the “heart” when used metaphorically. [55] (The biblical data do not warrant seeing the heart as a consti-tuent element in man, distinct from the soul or spirit.) Affections relate to one’s values and are expressed through the

47

moral imperative of love. Man is to not love the world system (in its opposition to God), but to love God and people. Love for God is to be with all of one’s heart (Mark 12:30).

The Body

The material part of man is the one most easily identified and described. Since it can be examined empirically, the nature of the body can be described in the science of anatomy (which is beyond the scope of this paper). In addition to scientific knowledge about the physical part of man, we have many references to it in Scripture, some of which were surveyed in the previous chapter. Dichotomists and trichotomists agree on the nature of the body as man’s material part; together they disagree with monism which does not distinguish the soul as an element distinct from the body.

L. T. Holdcroft defines the body as a house or vehicle in which man lives and through which he performs activities on earth. He also notes some distinctive features of man’s body, including the brain’s capabilities, an opposable thumb, and an upright posture.[56] The body will decompose at death:”. . .For out of it you were taken; For dust you are, And to dust you shall return” (Gen 3:19 ). At death the believer’s soul and spirit go to heaven to be with God (Phil 1:23; 2 Cor 5:6-10).

Man is designed to use the body as a servant to his immaterial nature. In fallen man the body craves its own gratification, so self-discipline is required. As Paul testi-fied, “But I discipline my body and bring it into subjection,

48

lest, when I have preached to others, I myself should become disqualified” (1 Cor 9:27). In contrast to Platonic trichotomy, the material body was created as good (Gen 1:31). Sexual relations of a husband and wife are an important aspect of marriage (Gen 1:28; 1 Cor 7:3-5); and food is to be received with thanksgiving (1 Tim 4:3). The Christian is responsible to use his body as an instrument of righteousness (Rom 6:12,13), which is an essential aspect of progressive sanctification (1 Thes 4:3-5).

Summary

This chapter has surveyed the three major models of man’s makeup, rejecting monism unequivocally. The case for dichotomy has earned it the status of being the usual position of evange-lical theologians. A basic description of trichotomy was given, with acknowledgement of some variant options within this model. Scriptural summaries of the parts of man were delineated, based upon a trichotomist view. To further trace out the implications of trichotomy, the next chapter will place it in the context of redemptive history, giving particular attention to exegetical evidence for the three parts of man.

Footnotes

1.Philip J. Hefner, “Forth Locus: The Creation,” in Church Dogmatics , ed.Carl E. Braaten and Robert W. Jenson (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984), 334.

2.Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1983), 524.

3. Everett F. Harrison, ed., Baker’s Dictionary of Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1960), s.v. “Trichotomy,” by Wayne Ward, 531.

4. Bruce Milne, Know the Truth (Downers Grove, IL: Inter Varsity Press, 1982), 97.

5. Hoekema, Created in God’s Image , 209-10.

6. Ibid., 212

7. Ibid., 209

8. Catechism of the Catholic Church (Liguori: Liguori Publications, 1994) 93; quoted in Boyd, “One’s Self Concept in Biblical Theology,” 209.

9.Calvin Seerveld, “A Christian Tin Can Theory of Man,” Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation 33 (1981): 74.

10.George J. Jennings “Some Comments on the Soul,” Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation 19/1 (1967): 7-11.

11. Jeffrey H. Boyd, “The Soul as Seen Through Evangelical Eyes,” Journal of Psychology and Theology 23 (1995): 161-70.

12. Erickson, Christian Theology , 526.

13. Boyd, “One’s Self Concept in Biblical Theology, ” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 40 (1997): 215.

14. Franz Delitzsch, A System of Biblical Psychology (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1867), 104-105.

15. Augustus H. Strong, Systematic Theology (Philadelphia: Judson Press, 1907), 485.

16. Milne, Know the Truth , 97.

17. Gordon R. Lewis and Bruce A. Demerest, Integrative Theology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1990), 148-49 quoted by Boyd, “One’s Self Concept in Biblical Theology,” 211.

18. Ibid.

19. Strong, Systematic Theology , 485.

20. Ibid.

21. L.Berkhof, Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1939), 192.

22. Ibid., 195

23. Gordon H. Clark, The Biblical Doctrine of Man (Jefferson, MD: The Trinity Foundation, 1984), 37.

24. Strong, Systematic Theology , 486.

25. Ibid.

26. J. O. Buswell, A Systematic Theology of the Christian Religion (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1962), 1:240.

27. Paul Enns, The Moody Handbook of Theology (Chicago: Moody Press, 1989), 307.

28. J. B. Heard, Tripartite Nature of Man: Spirit, Soul and Body (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1875), 116,120.

29. L. Thomas Holdcroft, Anthropology: A Biblical View (Clayburn, BC: Cee Picc, 1990), 20.

30. The Scofield Reference Bible , ed. C. I. Scofield (NY: Oxford University Press, 1909), 1270.

31. G. H. Pember, Earth’s Earliest Ages (Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1942), 77.

32. Mark Cambron, Bible Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1954), 158.

33.Lewis S. Chafer, Systematic Theology (Dallas, TX: Dallas Seminary Press, 1947), 2:181.

34. Ibid.

35. Henry C. Thiessen, Lectures in Systematic Theology (Grand Raids: Eerdmans, 1949), 227.

36. Buswell, A Systematic Theology of the Christian Religion , 1:247.

37. Franz Delitzsch, A System of Biblical Psychology , 99.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid., 109.

40. Ibid., 116.

41. Ibid., 115-16.

42. Ibid., 117.

43. J. B. Heard, The Tripartite Nature of Man , 104.

44. Clarence A. Beckwith, “Biblical Conceptions of Soul and Spirit” in The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge , ed. Samuel M. Jackson (NY: Funk and Wagnalls, 1911), 11:12.

45. L. Thomas Holdcroft, Anthropology: A Biblical View , 23-24.

46. Oswald Chambers, Biblical Psychology , 2d ed. (Grand Rapids: Discovery House, 1995), 46.

47. Ibid., 210.

48. Ibid., 33.

49. Watchman Nee, The Spiritual Man (NY: Christian Fellowship Publishers, 1968), 2:8.

50. The Scofield Reference Bible , 1270.

51. T. Austin Sparks, What is Man? (Cloverdale, IN: Ministry of Life, n. d.), 38.

52. J. B. Heard, The Tripartite Nature of Man , 351.

53. Jessie Penn-Lewis, Soul and Spirit (Fort Washington, PA: Christian Literature Crusade, 1992), 13.

54. Kenneth Liu, A Study of the Human Soul and Spirit , unpublished thesis for Talbot Theological Seminary, 1966, 58; quoted in Holdcroft, Anthropology: A Biblical View , 25; see also Pember, Earth’s Earliest Ages , 75.

55. For a trichotomistic model that uses “heart” rather than a human “spirit,” see Neil T. Anderson and Robert L. Saucy, The Common Made Holy (Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 1997), 79-100, 156.

56. L. Thomas Holdcroft, Anthropology: A Biblical View , 21

by John B. Woodward

www.gracenotebook.com

copyright 2000