Fellowship

[“There is therefore now no condemnation to those who are in Christ Jesus…” Romans 8:1]

To be “in Christ” in this sense is to have the consciousness of His favour. This is a matter, not of standing, but of experience — and yet not of feeling, but of faith. We are commanded to “abide” in Christ. That which has reference to our judicial standing cannot be a matter of exhortation. Those who have taken their stand in Christ — who are justified — are now required to remain, to dwell, or abide in Him for sanctification. The “in Christ” which has to do with our experience and walk, which relates to our sanctification, is constantly a matter of exhortation in the Scriptures.

It is possible, alas! not to abide in Him. And what happens when the believer ceases to abide? He then lives the self-life.

There is such a thing as a religious self-life. Is it not the life that is too often manifested, even by those who have a saving knowledge of Christ? There may be a clear apprehension of what it is to be “in Christ” as to justification, and yet much darkness and perplexity as to the “in Christ” of sanctification. Many have a true aim, seeking to glorify Christ, and to be made like Him; they have sincere and earnest desires, and they are making constant and vigorous efforts after holiness; and yet they are continually being disappointed. Failure and defeat meet them at every turn. Not because they do not try, not because they do not struggle, — they do all this, — but because the life they are living is essentially the self-life and not the Christ-life.

They are brought into condemnation. This arises from the fact that the “law of sin” in their members is stronger than their renewed nature.

The soul that ceases to abide in Christ lives the “I myself” life. The words, “them which are in Christ Jesus,” form a contrast to the expression, I as I am in myself, in the seventh chapter, twenty-fifth verse (Godet’s commentary).

“I myself” — “apart from and in opposition to the help which I derive from Christ” (N. T. Commentary, edited by Bishop Ellicott) — I myself am conscious of a miserable condition of internal conflict, between two opposite tendencies — the two natures: the one consenting to the law that it is good, delighting in it, and desiring to fulfill its requirements; the other drawing me in the contrary direction, and; being the more powerful of the two, actually bringing me into captivity to the law of sin, and thus resulting in a condition of condemnation.[1]

“I in myself.” “This expression is the key to the whole passage (Rom. 7. 14 – 25). St. Paul, from verses 14 to 24, has been speaking of himself as he was in himself.” (Conybeare and Howson.)

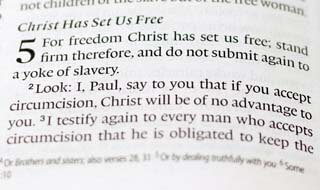

“There is therefore now no condemnation.” “This word no (aucune),” as Professor Godet observes, “shows that there is more than one sort of condemnation, resting on the head of him who is not in Christ Jesus. There is, first, the Divine displeasure excited by the violation of the law — the anger described in the first three chapters of the Epistle to the Romans. The two following chapters represent to us the removal of this condemnation by the blood of Christ, and by the faith that consents to come and draws its pardon thence [Romans 4,5].

“But if, after this, sin continues the master of the soul, condemnation will infallibly revive. For Jesus did not come to save us in sin, but from sin. It is not pardon which constitutes the health of the soul, it is salvation, it is the restoration of holiness. The reception of pardon does not affect our resemblance to God; holiness alone does this. Pardon is the threshold of salvation, the means by which convalescence is begun. Health itself is holiness.

“If then, the first condemnation to be taken away is that of sin as a fault, the second, which must necessarily be removed too in order that the first may not return [subjectively], is sin as a power, as the inwrought tendency of the will. And it is the removal of this second condemnation that St. Paul here describes: ‘for the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has made me free from the law of sin and death.'” [Rom. 8:2]

In this “I myself” life, the evil tendency gains the ascendancy. So that though with the new nature, the inner man, or the mind, we serve the law of God, yet we are nevertheless overcome, and are practically brought into captivity to the law of sin. Such a life must of necessity be a life of [subjective] condemnation in the daily experience.

But another characteristic belongs to this self-life. It is essentially carnal (sarkikos) (Rom. 7. 14. See Appendix, A, Note B), not carnal in the sense of being unregenerate. A carnal man may be also one who has been born of the Spirit, but is not sufficiently actuated by His enlightening and sanctifying power to overcome the hostile power of the flesh; he still thinks, feel, judges, acts, “according to the flesh” (Lange’s Commentary on 1 Cor. 3. 1).

The condition described by “carnal” may be either the immature stage of the young convert, or a state of relapse into which the more advanced believer has fallen. To the first no blame can be attached, for all must pass through this stage in their progress from the natural to the spiritual. But to the second condemnation belongs, as we see from the way in which the Apostle writes to the Corinthian believers, “I could not speak unto you as unto spiritual, but as unto carnal, even as unto babes in Christ” (1 Cor. 3:1).

“He is here not speaking of Christians as distinguished from the world, but of one class of Christians as distinguished from another” (Hodge).

This is the description of every believer, even an apostle, regarded as he is in himself. And such is the experience of the believer when he lives out of fellowship with Christ. The carnal or fleshly principle gains the ascendancy. He is no longer spirit, soul, and body, but rather body, soul, and spirit, the order being reversed, the lowest principle becoming dominant.

To be “in Christ” as to fellowship is to have the individual human spirit apprehended, or laid hold of, by the Holy Spirit of God. We are thus not only brought into harmony with God, but linked with the power of God. The ability we lack when we struggle to overcome in the self-life is no longer lacking in the Christ-life. This is to be free from the law of sin and death — this is to be spiritually-minded.

Part 2 of 2. This article is an excerpt from The Law of Liberty in the Spiritual Life, chapter 2, by Evan Hopkins. “Hopkins (1837-1918), was an evangelical Anglican vicar whose ministry spanned 52 years, is best known for his faithful Bible-conference ministry throughout the British Isles.” The book is online at Gracenotebook.com and in print from CLC Publications