by Evan H. Hopkins

Contents: Links to the chapters on GraceNotebook.com

Ch. 6. CONFORMITY TO THE DEATH OF CHRIST

Ch. 10. FILLED WITH THE HOLY SPIRIT

NOTE A

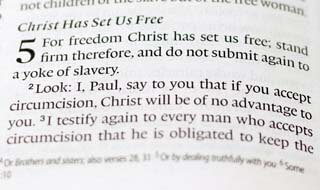

SUBSTITUTION of Christ. – Canon Liddon has a valuable remark in one of his sermons: “‘He loved me, and gave Himself for me.’ The Eternal Being gave Himself for the creature which His hands had made. He gave Himself to poverty, to toil, to humiliation, to agony, to the cross. He gave Himself (Gk. huper emou) for my benefit; but also Ź – Á µμ¿Í, in my place. In this sense of the preposition St. Paul claimed the services of Onesimus as a substitute for those which were due to him from Philemon – (Gk. hina huper sou moi diakone (Cf. Bp. Ellicott on Gal. iii. 13). Such a substitution of Christ for the guilty sinner is the ground of the Satisfaction which Christ has made upon the cross for human sin. ” – Liddon: “University Sermons,” p. 239.

NOTE B

“According to Meyer, sarkinos [fleshly] designates the unspiritual state of nature which the Corinthians still had in their early Christian minority, inasmuch as the Holy Spirit had as yet changed their character so slightly that they appeared as if consisting of men of flesh still.

“But sarkikos expresses a later ascendancy of the hostile material nature over the Divine principle of which they had been made partakers by progressive instruction. And it is the latter which, as he (Meyer) thinks, the apostle makes the ground of his rebuke. In so far, however, as both epithets are of kindred signification, he could, notwithstanding the distinction between them, affirm ‘for you are yet carnal.’ ” – Lange on 1 Cor. iii.

“But that the term sarkinois is to be here understood relatively, and as not denoting an entire lack of the ¹νµÍμ± is clearly indicated by the phrase, ‘As unto babes in Christ.’

“They were sarkikoi at first, but not developing their spirituality they became sarkoiki, Lange.

According to Delitzsch “sarkinos is one who has in himself the bodily nature and the sinful tendency inherited with it; but sarkikos is one whose personal fundamental tendency is this impulse of the flesh.”

Bengel quotes Ephraem Syrus: “The apostle calls men who live according to nature, natural, psuxikous; those who live contrary to nature, carnal, sarkikous; but those are spiritual pneumatikoi, who even change their nature after the spirit.”

NOTE C

“That the apostle ascribed to man a pneuma [spirit] belonging to his nature is clear from 1 Corinthians ii. 11, where he speaks expressly of pneuma tou anthropou. It is the principle of knowledge and self-consciousness, the same which he elsewhere terms nous; but here designates as pneuma in order to draw a parallel between the Pneuma tou Theou and the pnuema tou anthropou” – Prof. Dickson on “St. Paul’s Use of the Terms Flesh and Spirit,” pp. 22, 23.

“The question, whether the natural man has a pneuma... is to be answered roundly in the affirmative, on the ground of various passages quite unambiguous (such as 1 Cor. ii. 11, v. 4, vi. 20, vii. 34; Rom. viii. 16). These passages also give us significant hints as to its nature. It is specifically distinguished from the Divine pneuma, as it needs comfort and rest (2 Cor. ii. 12, vii. 13); it may be deified and require purification (2 Cor. vii. 1); it is assumed that it needs to be sanctified and preserved (1 Thess. v. 23); and the possibility of its not being saved is plainly implied (in 1 Cor. v. 5).” – Prof. Dickson (above quoted), pp. 56, 57.

NOTE D

“The GREEK AORIST [tense] expresses an action or event rounded off and complete in itself. ‘A point in the expanse of time,’ whether in the past, the present, or the future, but especially in the past.” “The aorist tense therefore expresses complete action. It may cover a single act, or a series of acts. If the former, it denotes the act not as in progress but as complete. If the latter, it represents the series as concluded, rounded off, wound up, condensed to a point. The aorist always denotes a point in contradistinction to a line. This force is essential to it in all the moods.”

NOTE E

“Christ not only grew in wisdom and stature like other men, but underwent the ordinary process of discipline by which virtue is matured and attains its due reward; He grew ethically, as well as physically and intellectually. He rendered meritorious obedience, and earned the crown by enduring the cross (Heb. xii. 2). The teleiosis [goal] of which the Epistle to the Hebrews speaks (v. 9) implies a previous state of relative imperfection: what can this be in One whom we believe to have been sinless?

“It must be considered as negative, not positive; as analogous to the imperfection of the first Adam before he underwent his trial. Virtue, to prove itself such, must be tried; and the severer the trial the greater the result if resistance to sin is successful. The second Adam, like the first, must pass through the furnace. He must be tempted, and overcome the temptation, endure sufferings which culminate in death, ‘learn obedience by the things which He suffered’ (Heb. v. 8), and to become ‘perfect’ (Heb. ii. 10) in a different sense from that in which He was before. He attained the perfection of a proved and triumphant virtue as distinguished from a state of untried innocence. And thus He became fitted, from His own personal experience, to be a ‘merciful and faithful High Priest in things pertaining to God.’“Introduction to Dogmatic Theology,” by Rev. E. A. Litton, late Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, p 227

Electronic edition courtesy of Al McPhee

Printed book available from: Christian Literature Crusade