[See Table of Contents and Appendix]

[See Table of Contents and Appendix]

“Sin is lawlessness.” – I John 3:4

“All unrighteousness is sin.” – I John 5:17

“Therefore do not let sin reign in your mortal body, that you should obey it in its lusts.” – Rom. 6:12.

“Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin.” – Ps. 51:2

“Who gave Himself for us, that He might redeem us from every lawless deed and purify for Himself His own special people, zealous for good works.” – Titus 2:14

“Heal my soul, for I have sinned against you.” – Ps. 41:4

“I will heal their backsliding.” – Hos. 14:4

“Knowing that you were not redeemed with corruptible things, like silver or gold, from your aimless conduct received by tradition from your fathers, but with the precious blood of Christ, as of a lamb without blemish and without spot.” – I Pet. 1:18, 19

“Now to Him who is able to keep you from stumbling, and to present you faultless before the presence of His glory with exceeding joy, to God our Savior, Who alone is wise, be glory and majesty, dominion and power, both now and forever. Amen.” – Jude 24, 25.

[Annotated: outline, bold, and bracketed content added for clarity – JBW. Page numbers are approximate to the Christian Literature Crusade edition.]

EVERY heresy, it has been said, has its root in defective views of sin. What we think of the Atonement depends greatly upon what we think of the evil which made that Atonement necessary. The converse, no doubt, is also true. But if we would rise towards a full appreciation of the value of that infinite sacrifice, we must seek to understand, as perfectly as possible, the true nature of sin.

What then is sin? So widespread and universal is the existence of evil, that we are apt to regard it as an inseparable adjunct to our human nature. But sin is not an essential element in the constitution of our humanity. We know that it was not in man originally, nor will it be in man as finally glorified; neither did it exist in the Man Christ Jesus. And yet there is scarcely a fact of which we are more conscious than the presence of evil. It meets us on every hand. Its desolating influence is seen and felt by all. Sin is no mere figment of the imagination; it is a terrible reality. It is no vague, indefinite shadow; it is a real and specific evil.

16

Nor again are we to regard sin as a necessary constituent of our moral progress. That it is overruled for our good, and that it is made to serve in the process of our spiritual discipline, is undoubtedly true; but sin is not an essential element in our moral training or spiritual advancement. We need not sin that grace may abound; we need not be under its power, nor defiled by its taint, in order to be advancing in knowledge or growing in humility.

To learn its true nature we must look at it, not only in relation to ourselves, but in relation to God; we must regard it in connection with His infinite justice, and holiness and love.

It is only in that light that we shall understand its real character. We must consider it, moreover, in more than one aspect. It is such a vast evil, that we can form no adequate conception of its nature unless we look at it from various points of view. Sin has many aspects.

But from whatever side we contemplate it, we shall see that the characteristic feature of each aspect [of sin] is met by a corresponding fitness in the remedy which God has provided for sin.

[1] It is one thing to recognize the effects of sin on mankind, it is another thing to see it in its essential character, as rebellion against God. Man through sin has not only become “wounded and debilitated,” he has become alienated from God; he has been brought into an attitude of positive antagonism to God. Sin therefore is not something which appeals to pity only, a mere misfortune; it is that which deserves punishment, for it is rebellion against the purity and goodness and majesty of God.

17

If sin were not an offence, we could conceive of the mercy of God forgiving sin without any sacrifice; but the necessity of a sacrifice teaches us that sin is a violation of God’s law. This necessity is set forth with unmistakable clearness in the Old Testament, and with equal emphasis in the New.

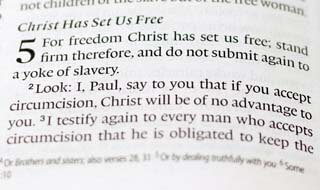

“Sin is the transgression of the law” (I John iii. 4). By the law we are to understand, “not only the Mosaic law of the Old Testament, but also the law of the New Testament in Christ, and by Him explained in the word and exhibited in the life, as the law written in man’s heart for his special direction; it embraces the whole complex commandment” (Pearson).

Man feels within himself just what God has revealed in His word – that sin needs something more than the mercy of God. In this respect the doctrine of the Bible and the witness of the human heart are one.

It is a true instinct of man’s nature that teaches him that guilt needs compensation; but the mistake into which he falls, if left to himself, is that he seeks to make that compensation by means which he himself has devised. This is the history of all heathen sacrifices.

Sin is an offence, because it is rebellion against the sovereignty of God, a contradiction to His nature, an insult to His holiness. It stands related to law – not merely to the law of reason, or of conscience, or of expediency, but to the law of God. Sin consists essentially in the want of conformity to the will of God, which the law reveals; it is lawlessness – a breach of law. And thus, it is the law that reveals the sinfulness of sin. “The crookedness of a crooked line may be seen of itself, but it is still more evident if compared with a perfect standard of straightness.”

18

While the voice of conscience tells us that some amends is needed for the guilt of our sin, it is only revelation that shows us how that amends can be made; it is only there that we learn what sacrifice is sufficient to atone for human guilt. This view of sin leads us to see the meaning of Christ’s death on the cross. It was the death of a condemned criminal: “He was wounded for our transgressions, He was bruised for our iniquities” (Isa. liii. 5); He died, “the just for the unjust” (I Pet. iii. 18).

Freedom from sin as a transgression, as an offence against God, consists then in this – that through Christ’s atoning death it is so “put away” as “to make it as though it had never been.” “No power in earth or heaven can make that not to have been done which has been done; the only imaginable and conceivable alteration is, that it should be as though it had never been done, that all bad effects of it should be destroyed and obliterated, and that the sin should be nullified by compensation.” (Mozley.) This freedom from sin as an offence we enter into as a present privilege. It is the first aspect of liberty which we are brought to experience through a saving view of Christ’s death upon the cross.

Sometimes the term sin is used in Scripture as having reference to acts of sin. This, however, is not the only sense in which sin is spoken of…

[2] It is also referred to as a power, dwelling and working in man.

When we speak of sinning, we imply, of course, an action. But by an action we do not mean merely that which is external; it may be a purely inward one. Transgression therefore must not be limited to outward violations of God’s law; it includes all those inner activities of the soul which are opposed to the mind and character of God.

19

In the sixth [chapter] of Romans the particular aspect in which sin is contemplated is that of a ruling power. Sin is there personified as one who seeks to have lordship over the believer.

Consider what it is that the fall has involved. It has not only brought upon man the penalty due to sin as an offence, it has enslaved him under sin as a ruling principle. Sin is a power that has entered into the central citadel of a man’s being, and, establishing itself there, has brought every part of his nature under its sway. Sin is a principle that is essentially opposed to God, and by taking possession of man’s will and affections, makes him an enemy to God, and leads him out into open rebellion against Him. [unredeemed] Man has thus become a slave to sin.

From the central part of our nature [the unregenerate human spirit] sin reigns over the whole man. Our body is thus “the body of sin” (Rom. vi. 6. “The body of (belonging to) sin.” . . . “The material body . . . as the inlet of temptation and the agent of sin.” – Dean Vaughan): for while we are under sin’s dominion, the body is the instrument through which sin carries out its work; it is in sin’s possession and under sin’s control.

In this sixth chapter to the Romans the Apostle sets forth the believer’s present position in reference to sin. The Cross of Christ has completely changed his relation to sin.

Christ’s death, which has separated the believer from the consequences of sin as a transgression, has also separated him from the authority of sin as a master – set him free.

20

The believer sees that Christ, by dying for him, has completely delivered him from the penalty of sin. So it is his privilege to see that because he is identified with Christ in that death, he [the believer] is also delivered from sin as a ruling principle. Its power is broken. He is in that sense “free from sin” (Rom. vi. 18, 22).

The purpose of the Apostle, in this sixth chapter, is to show how completely the believer is identified with Christ when “He died unto sin.” To enter fully into the meaning of that death is to see that Christ has emancipated us from any further dealings with our old master sin. The believer is privileged thus to take his place in Christ, who is now “alive unto God.” From that standpoint he is henceforth to regard sin. He is now and forever free from the old service and the old rule. The Cross has terminated the connection once for all, and terminated it abruptly. It has effected a definite and complete rupture with the old master, sin.

“Such is the Divine secret of Christian sanctification, which distinguishes it profoundly from simple natural morality. The latter says to man, Become what you would be. The former says to the believer, Become what you are already (in Christ). It puts a positive fact at the foundation of moral effort, to which the believer can return and have recourse anew at every instant. And this is the reason why his labour is not lost in barren aspiration, and does not end in despair.

“The believer does not get disentangled from [the authority of] sin gradually; he breaks with it in Christ once for all. He is placed by a decisive act of will in the sphere of perfect holiness, and it is within it that the gradual renewing of the personal life goes forward. This second gospel paradox, sanctification by faith, rests on the first, justification by faith” (Professor Godet on Romans vi).

21

The Cross is the efficient cause of this deliverance. Freedom from sin’s ruling power is the immediate privilege of every believer. It is the essential condition or starting point of true service, as well as of real progress. Such service and growth are as possible for the young convert as for the mature believer. Therefore freedom from sin’s dominion is a blessing we may claim by faith, just as we accept pardon. We may claim it as that which Christ has purchased for us, obtained for our immediate acceptance. We may go forth as set free from sin, and as alive unto God in Jesus Christ our Lord. This is freedom from sin as a ruling principle.

It is possible to see in the death of Christ an all-sufficient atonement for sin, and yet not to see that in that death we have also the secret or source of personal purification of sin.

[3] Sin is not merely a load that weighs us down, or an offence that has brought upon us penal consequences. It is an uncleanness that makes us unfit for God’s presence. We may have rejoiced in the fact that the load is gone, that the guilt has been atoned for, and yet we may know but little of Christ’s power to cleanse. Owing even to one single act of disobedience we may have been thrown out of communion. We have thus become conscious, not only of guilt, but of defilement.

How vividly all this comes out in God’s dealings with Israel under the old covenant!

It is impossible to read the book of Leviticus, for example, without being struck with the emphasis there laid on the necessity of being separated from ceremonial defilement.

22

We notice in the directions there given how jealously Jehovah watched over His people in this matter. The most minute details are entered into respecting their food, their raiment, their habits, and other domestic arrangements. All this we know was significant of something far deeper than that which was merely physical or ceremonial. It is in the light of the gospel that we learn their full and true import.

Looking at the whole question of defilement, we notice that it arose from two distinct sources – external and internal.

The defilement that arose from within is chiefly dwelt upon in the Book of Leviticus. This has reference to the moral defilement that springs from indwelling evil. And the defilement that arose from without, through external contact with death, is brought out more especially in the book of Numbers. There we have in type the defiling effects incurred by contact with the world.

In reference to the former, defilement arising from within, the most striking picture is that presented by the leper. Nothing could more forcibly impress Israel of old with the loathsome nature of sin, than this fearful disease.

Such a one would be excluded from the sanctuary. He was shut out from the worship of God, and from all intercourse with the people of God.

So with the man who had come in contact with death (Num. xix), whether intentionally, through negligence or unconsciously. He became at once ceremonially unclean, and was “cut off” from all the privileges of a redeemed worshipper.

23

Is it not so now?

The body in these types stands as an image of the soul. Ceremonial defilement and cleansing represented spiritual pollution, and the purification revealed to us in the gospel.

The suspension of a believer’s communion is that which answers to the cutting off of a member from the congregation of Israel.

In all these pictorial unfoldings of the gospel, God was teaching His redeemed people that He could not tolerate any uncleanness upon those whom He had brought unto Himself, and amongst whom He had taken up His abode. And because He required His people to be holy He made a special provision for their purification.

Whether we speak of the defilement that comes from within, or that which arises from without, God had provided means by which all uncleanness might be ceremonially removed. And this provision God made with this view, that His people might walk before Him in close and abiding fellowship.

Now if such privileges were real under the Old Testament dispensation, how much more real are they under the New!

We must never lose sight of this central fact, that the true basis of all purification is found in the atoning death of Christ. There are not two fountains, two sources of life and purity. There is but one central spring, and that is the Cross.

It was to this both rites pointed – the law relating to the cleansing of the leper, and the ordinance of the red heifer [Num. 19:2]. The place where the forgiveness of sins is found is the source whence cleansing from defilement is obtained.

24

It was by a definite and personal appropriation of the Divinely appointed provision that both the leper and the man who had come in contact with death were cleansed and restored to fellowship with God. Nothing that the Israelite could devise was able to effect such a restoration, for no other means could remove the ceremonial uncleanness.

So it is only in the Cross of Christ that a power can be found capable of separating the soul from all moral defilement.

And because such defilement throws the soul out of communion with God, all Christian duties performed in that condition, however scrupulously discharged are but “dead works,” for they have no breath of spiritual life.

As it is our privilege to know that we are reconciled to God by the death of His Son, so it is our privilege to see that by the same atoning death we are separated from the defilement of sin. The source of our pardon and justification is the source also of our purity. And if we know what it is to be freed from the penalty due to our guilt, so we may know what it is to be cleansed and to be kept cleansed, as to our inward consciousness, from all impurity. It is only thus that we can learn what abiding fellowship with God really means.

He “gave Himself for us, that He might redeem us from all iniquity” (Titus ii. 14). That is, Christ gave Himself as a ransom, to redeem us from the enemy’s power. Lawlessness is here regarded as the power from whose control we are set free. But this was not the only purpose of His death. “And purify unto Himself a peculiar people,” etc. The purification of those He died to redeem is also the end [goal] of His sacrifice. And both blessings are received in the same way.

25

How many who have grasped the first seem to fail in apprehending the second!

The “ashes” of the red heifer [used with the water of purification by the priest] were to be applied to the person defiled. In those ashes we have “the indestructible residue of the entire victim.” Those ashes included the blood, after the sacrifice was completed. They were available for the cleansing of the defiled Israelite. The death of the victim was not repeated. For that sacrifice pointed to the death of Christ, which was “once for all.” But the ashes were set apart for endless application. The “water of separation,” by which the virtue of the sacrifice was applied, was not water alone, but water impregnated with the “ashes.” The unclean was sprinkled with the water containing these ashes.

“What is the spiritual meaning of this? To what does it point? Not to two sources of spiritual relief, one for pardon, another for cleansing. Whether we look at the water as foreshadowing the Holy Spirit, or as referring to the word, the one central point to which all the lines of typical truth here converge is the blood, or the death, of Christ. Is not this the reasoning in the ninth of Hebrews?

If the Old Testament rite effected the cleansing which had reference to ceremonial defilement, “how much more shall the BLOOD of Christ . . . purge your conscience from dead works to serve the living God?” (Heb. ix. 13, 14).

26

We may insist, as some do, that the water in this type refers to the word. This does not detract from the virtue of the blood. As the water carried the ashes, the ashes that contained the blood, and brought the unclean person in contact with the blood, so now it is the word that brings us to the blood of Christ. But the word is not the Fountain of our cleansing; it is only that which brings us to the Fountain. There is but one Fountain for sin and for uncleanness – the Cross of Christ.

What then we do we need in order that we may know the cleansing power of the Cross of Christ? Or, to put it in other words, how may we be separated in heart and mind, in our inner consciousness, from the defiling influence of sin? Only by an apprehension of this blessed fact, that Christ died in order to separate us from sin’s defilement.

To be cleansed from any impurity is just to be separated from it. Nothing can separate from sin but the death of Christ. The fact and the purpose of that death are revealed in His word. To bring us into conformity with that death is the office of the Holy Spirit through the word. This is to know the liberty of the cleansing power, as well as the freedom from the atoning efficacy of Christ’s sacrifice for sin.

[4] It has often been shown that sin is to the soul what disease is to the body. The effect of disease on our physical organism is just a picture of what sin produces on our spiritual nature. Sin as a moral defilement has already been touched upon in connection with leprosy. What we have now more especially to consider is the paralyzing or disabling effect of sin.

27

It will help us to understand what sin is in this special aspect, and what it is to be freed from its disorganizing effects, if we look at our Lord’s miracles as symbols of spiritual healing, illustrations of what He is now doing upon the souls of men. These miracles were not merely manifestations of Divine power. They were “signs” of spiritual truth. They were significant of something far higher than mere physical cures. Nor must we limit our interpretation of them to that of “conversion.” In the majority of instances they set forth the blessings to be known and realized by those who are God’s children. Disease supposes the existence of life. What is disease but life in an abnormal or morbid condition? Disease has been defined as “any state of the living body in which the natural functions of the organs are interrupted or disturbed.” Every cure that our Lord wrought was an emancipation of a part, or the whole of the body, from such a state of derangement, and represented the liberation of the soul from some particular form of moral evil.

In the eighth chapter of St. Matthew, we have an account of a series of miracles which our Lord wrought immediately after He had preached His sermon on the mount. Having unfolded the principles of His kingdom by teaching, He then shows His power by His actions, and communicates His liberating and energizing virtue by healing all their diseases. We have here in this chapter leprosy, paralysis, fever, and other forms of evil; but Christ was able to cure them all.

What did those physical ailments set forth but different aspects of sin as a disease?

28

In the dysfunction of paralysis we see the loss of the power of voluntary muscular motion. It may be a loss of the power of emotion without a loss of sensation, or a loss of sensation without loss of motion, or a loss of both. It appears under different forms. Sometimes it attacks the whole system; at others it affects one side of the body; and at other times a single member only is affected.

Sin has precisely the same effect on our souls. Though there is spiritual life, there may be lack of spiritual vigour. The effects of sin may be traced in the impairment of voluntary power, and in the enfeebling of all moral energy, as well as in the hardening and deadening of the spiritual sense. And the result is the whole tone of the spiritual life is lowered. Sin thus robs us of the power by which alone we are able to perform the functions that belong to our renewed being. And it not only undermines our strength, it hinders our growth. The child may have all the parts of its body complete, every organ, every faculty, and yet it will fail to grow if struck down with paralysis. So with the soul. The new birth may have taken place, the great change of conversion to God may have been clear and unmistakable, and yet sin may have been allowed to come in and produce its paralyzing effects. It not only robs us of all spiritual energy, it retards our progress, it hinders our growth.

But disease not only enfeebles and deadens the vital powers, it may bring about positive defects in the bodily organism. Take, for instance, the case of the man born blind, or of the one who was deaf and dumb. Here we see something further than the mere weakening or paralyzing consequences of disease. So with sin. We may look at it from this point of view – as a privation. This we see in the unregenerate and also in the regenerate. It may so affect the spiritual organs of our moral being that in course of time these organs cease to act. The words, “having eyes they see not,” become actually fulfilled.

29

In the case of the deaf mute, what a picture we have of spiritual things! “They bring unto Jesus one that was deaf, and had an impediment in his speech.” He was incapable of hearing or of speaking. He was destitute of two of our noblest faculties. The organs were there, but practically the man was as if they were not. Two channels of communication with the outer world were thus closed to him.

How did He effect the cure? What was the order of the deliverance? With which organ did He begin? He first opened the ear. Now the ear we know is an organ of reception. This is its design. It is made for the purpose of receiving, not of giving. It is the channel by which impressions pass into the mind from without.

The man was destitute of the power of receiving sounds. The organ was not wanting, but it was disorganized. The doors were closed – the avenue was blocked up. He was insensible to all such impressions.

It is so spiritually. Sin has robbed man of his power of hearing God’s voice. And sin will rob the believer, if he yields to it, of the same faculty – hearkening to the voice of the Lord.

To hear is the first act of faith. “Hear, and your soul shall live.” “He who hears My word and believes in Him who sent Me has everlasting life.” And hearkening must go on throughout the whole life.

Then the Lord Jesus loosed his tongue.

30

The tongue is the instrument of speech. The man was destitute of the power of communicating his thoughts. It is the faculty by which we tell out what we have realized by taking in. It is the instrument we use when we sing to God’s praise, when we give utterance to our gratitude, and when we bear witness before men. It is of all others the organ which the messenger requires who goes forth to proclaim the glad tidings of salvation.

Now all this finds its parallel in the spiritual life.

Sin had robbed man of the power of giving praise to God, or of calling upon Him in prayer. It has deprived him of the ability of testifying to men. It has closed his mouth, it has made him dumb as well as deaf.

Now these two faculties – hearing and speaking – are mutually dependent. When people are born deaf, they usually remain dumb. an inborn faculty, but speaking – that is, articulate speech – is an acquired art. Man learns to speak by hearing. But how can he learn without hearing, and how can he hear if he is born deaf?

So there is an intimate connection in the spiritual life between the similar faculties of the soul.

The ears must be unstopped before the mouth is opened. Effective speaking for God depends upon right hearkening to God. It is by hearkening the heart is filled. And it is out of the abundance of the heart that the mouth speaks.

Jesus said, “Ephphatha,” Be opened [Mark 7:34]. Both the ears and the tongue were set free.

That act was symbolical of the whole of Christ’s ministry. He came, not only to redeem the soul, but to liberate every power and faculty we possess, and which God originally created for His glory.

31

Satan’s great aim is to enslave and carry into captivity. He seeks to close every avenue which brings the soul into intercourse with God. Christ has come to open the prison doors – to burst the fetters that keep the soul in slavery to sin. “The effect of His ministry was one continual Ephphatha” – the emancipation of every moral and spiritual power, the loosening of every chain.

[5] We all acknowledge the power of habit. Experience teaches us that the actions, and especially the oft-repeated actions, of days gone by, are a real power in us to-day. “The present is the resultant of the past.” Habit is the power and ability of doing anything acquired by frequent repetition. What at first was difficult, and imperfectly performed, by habit becomes easy, and is executed thoroughly.

Habit, therefore, is an acquired power, and is the result of repeated action. It is often like a second nature.

It is clear from this that we are not born with habits, though we inherit that which gave rise to them. Evil habits must not therefore be confused with those sinful tendencies with which every child of Adam comes into the world. We are born with the sinful tendency, but we are not born with the sinful habit.

“Man is a bundle of habits.” But his conduct is the result of something more than mere habit. Perhaps it would be impossible to exaggerate the power exercised by habit on our daily life. And yet it is of the greatest importance that we should recognize the clear distinction that exists between the inherent tendency and the acquired habit. Every evil habit may be entirely laid aside; we may be completely delivered from the power of any habit. But this does not mean that the tendency to sin is thereby eradicated.

32

Now there is a very close connection between acquired habits and desires. “If a bad set of habits have grown up with the growth of the individual, or if a single bad tendency be allowed to become an habitual spring of action, a far stronger effort of violation will be required to determine the conduct in opposition to them. This is especially the case when the habitual idea possesses an emotional character, and becomes the source of desires, for the more frequently these are yielded to, the more powerful is the solicitation they exert. And the Ego may at last be so completely subjugated by them as scarcely to retain any power of resistance, his will being weakened by the habit of yielding, as the desire gains strength by the habit of acting upon it” (Carpenter’s Mental Physiology).

Thus we see “by means of habit, passion builds its body, and exercises as well the spiritual as the bodily organs for the service of sin” (Martensen’s Christian Ethics). “The union of habit and passion is vice, in which a man becomes a bondman to a particular sin. In the language of daily life, one is accustomed to designate only those sins as vices that dishonour a man in the eyes of the world, like drunkenness, thieving, unchastity, and the like; as also one understands by an irreproachable, spotless walk in general, merely one that shows no spot on the robe of civil righteousness.

“But why should not one be at liberty to designate every sin as vice that gains such a dominion over the man that he becomes its bondman? Why should not pride, envy, malice, gossip (evilspeaking), unmercifullness, not be called vices – that is, when they have gained such a dominion that the man has forfeited his freedom?” (Ibid.).

33

In his Epistle to the Ephesians, St. Paul enumerates a number of sins, all of which may be included under the heading of acquired habits (Eph. iv. 25 – 32). Falsehood, theft, corrupt speech, bitterness, wrath, anger, clamour, railing, malice – all these are to be laid aside, not subjugated or kept under, but altogether put away, as things with which the believer has nothing more to do, and from which he is to be actually separated. “Wherefore putting away” – that is, stripping off – all these sins – as one puts off clothes. The very desire to yield to them may be removed.

The Apostle Peter, when he presses upon his readers the privilege and duty of holiness, brings them at once to the Cross of Christ. This is his argument: “Be holy, for I am holy” “knowing that you were not redeemed with corruptible things, like silver or gold, from your aimless conduct received by tradition from your fathers, but with the precious blood of Christ, as of a lamb without blemish and without spot.” (1 Pet. i. 16, 18, 19).

We may thus claim, as one of the benefits of Christ’s death, complete and immediate deliverance from the evil power of our past manner of life. Christ died to redeem us from every evil habit of mind and of body – from every false or dishonest course of action – from every vain or untrue line of conduct – from every base or impure motive.

34

[Clarification: maintaining a condition of victory by faith in Christ as Life does not infer this condition as a once-for-all victory or promise sinless perfection in this life.]

It is sometimes asked by those who entertain the idea that sin can be absolutely eradicated, “How can sin and holiness dwell together in the same heart? How can a man be sick and well at one and the same time? Is he not freed from disease when he is in perfect health? And may it not be said of the soul on whom Christ has laid His healing hand that, being made ‘whole,’ sin as a disease is entirely removed?”

The inference, therefore, is that all sin – not only as a transgression, but as a principle – is eradicated, when the soul is living up to its true privileges.

The “law of sin” then, it is said, no longer exists. The very tendency to evil is destroyed.

No one questions our liability to sin. Even Adam in his original sinless and innocent condition was not free from the liability to sin.

But there are some who seem to think we may be freed in this life from all tendency to sin. There are some who seem to maintain that the blessing of being “pure in heart” is a state of purity, rather than a maintained condition of purity. The distinction is important.

It may be made clear by an illustration. Let us suppose a natural impossibility; namely, that by passing a lighted candle through a dark room, such an effect is produced by that one act, that the room not only becomes instantly lighted, but continues in a state of illumination. If this were possible, the room would not be dependent on the continued presence of the lighted candle for its light, though it would be indebted to the candle in the first instance for the state of light introduced into it.

35

Such is not, we maintain, the nature of the cleansing which Christ bestows upon us.

Adopting the same illustration – but without supposing an impossibility – let the darkness represent sin, and the light holiness. What the lighted candle is to the dark room, Christ is to the heart of the believer [before glorification].

By the light of His own indwelling presence He keeps sin outside the region of our consciousness. The cleansing thus brought about and realized is not a state, but a maintained condition, having no existence whatever apart from Christ Himself.

When a light is introduced into a dark chamber the darkness instantly disappears, but the tendency to darkness remains; and the room can only be maintained in a condition of illumination by the continual counteraction of that tendency. The chamber is illuminated by “a continual flow of rays of light, each succeeding pencil of which does not differ from that by which the room was first illuminated.”

Here then we have, not a state, but a maintained condition, and an apt illustration of the law of entire and continual dependence.

If it were a state of purity that Christ produced in the soul, then we could conceive of it as having an existence apart from the present activity of His indwelling. And to what would such a notion inevitably lead? To the habit of being occupied with a state of purity rather than with Him who is made of God unto us “sanctification.” Then the delusion follows as a natural consequence, that we need not depend upon Christ continually for the counteraction of the ever-present tendency to evil, “the law of sin and death.”

36

“We are prone to imagine,” writes Professor Drummond, “that nature is full of life. In reality, it is full of death. One cannot say it is natural for a plant to live. Examine its nature fully, and you have to admit that its natural tendency is to die. It is kept from dying by a mere temporary endowment, which gives it an ephemeral dominion over the elements – gives it power to utilize for a brief span the rain, the sunshine, and the air. Withdraw this temporary endowment for a moment, and its true nature is revealed. Instead of overcoming nature, it is overcome. The very things which appeared to minister to its growth and beauty now turn against it and make it decay and die. The sun which warmed it withers it; the air and rain which nourished it rot it. It is the very forces which we associate with life which, when their true nature appears, are discovered to be really the ministers of death.

“This law, which is true for the whole plant-world, is also valid for the animal and for man. Air is not life, but corruption – so literally corruption that the only way to keep out corruption, when life has ebbed, is to keep out air. Life is merely a temporary suspension of these destructive powers; and this is truly one of the most accurate definitions of life we have yet received – ‘the sum total of the functions which resist death.’

“Spiritual life, in like manner, is the sum total of the functions which resist sin. The soul’s atmosphere is the daily trial, circumstance, and temptation of the world. And as it is life alone which gives the plant power to utilize the elements, and as, without it, they utilize it, so it is the spiritual life alone which gives the soul power to utilize temptation and trial, and without it they destroy the soul” (Natural Law in the Spiritual World).

37

To understand the great principle here set forth is to grasp the key to the whole question. Here is the solution of the great mystery. How can the tendency to sin exist in the presence of the indwelling Holy Spirit of God? By the law of counteraction. “The law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus hath made me free from the law of sin and death [Rom. 8:2] ” The very fact that the “law of the Spirit of life” is in force, and is ever a continual necessity, is a proof that the law of sin and death is not extinct, but is simply counteracted; in other words, that the tendency to sin is still there.

One ignorant of the laws of natural life might conclude that a plant, while manifesting the activity and freshness of vigorous growth, is absolutely free from the influence of those forces which tend to reduce it to a condition of death and decay. In other words, that so long as the plant is in the vigour of life, all tendency to die is destroyed, or non-existent, – that the only power then in operation, in fact, is the power of life. That might be the popular view of the matter. It certainly would not be the real condition of things. Let us not make a similar mistake in the matter of our spiritual condition.

Never in this life are we absolutely free from the presence of evil; the tendency to sin and death is ever with us.

As with the plant, so with the holiest saint: the vital principle had only to be withdrawn for an instant, and the natural tendency is at once apparent. Apart from Christ as the indwelling life, even the most advanced believer would at once relapse into a state of spiritual decay, because the law of sin would no longer be counteracted.

38

But, on the other hand, while recognizing the fact that we are not only liable, but prone, to sin – that we have to the last a downward bias – let us not forget that Christ is stronger than Satan and sin [1 Cor. 15:57]. By His death He has separated us from sin as to [1] its penalty, [2] its service, [3] its defilement, [4] its enfeebling consequences, [5] its habits; and so “in His life,” His indwelling life, He sets us free from its law. He so counteracts the natural tendency to sin by the law of the Spirit of life, that both its tyranny and strain are gone.

Christ’s death has for its end our separation from the evil. In those five aspects of sin we have here considered, we have endeavoured to show that freedom comes through the death of Jesus Christ.

But in this last aspect of sin, it is not absolute separation or eradication that the Scripture puts before us as our present privilege, but counteraction. It is not, therefore, to the death, but to the life of Christ, His risen life, that we are here directed. The law of the living Christ – that law into which we are introduced when we know what it is to be in vital fellowship with the risen Christ – sets us free and keeps us in a condition of freedom from the law of sin and death [Rom. 8:2].

*Chapter 1 questions for review and discussion:

1. What are the five aspects of sin that Evan Hopkins identified? (See annotated edition above)

2. How does God’s gracious remedy through the Cross of Christ answer each aspect of sin?

3. Why is it important to clarify that faith-based sanctification relates to the potential of maintaining a condition of victory over intentional sin patterns instead of the belief in eradication of one’s sin tendencies? (pages 34-38)

Studies on related issues:

The role of confession and repentance:

https://gracenotebook.com/the-christians-confession-of-sins/

The perfected and progressive aspects of the believer’s sanctification:

https://gracenotebook.com/the-perfected-and-progressive-aspects-of-the-believers-sanctification/

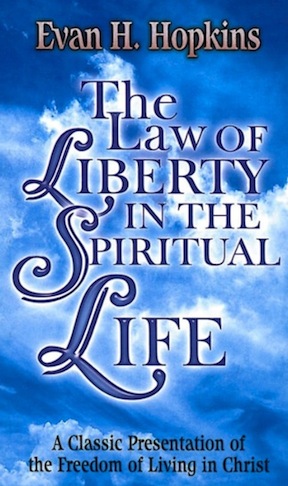

This page has a biographical sketch of Evan Hopkins:

https://gracenotebook.com/evan-hopkins-a-unique-gift-to-keswick-and-the-church/

The book can be ordered in paperback at

https://www.clcpublications.com/shop/the-law-of-liberty-in-the-spiritual-life/

* Questions and end notes added – JBW