The apparent contradiction in the doctrines of God’s sovereignty have occupied the hearts and minds of believers throughout history. Augustine’s refutation of Pelagius, the teaching of John Calvin and the eventual response of Jacob Arminius, the letters of doctrinal debate between the great evangelists John Whitefield and John Wesley–all show that this paradox resists simple answers. Nevertheless, perhaps a summary of the issues and a presentation of biblical checks and balances will be useful.

1. Summary of the doctrinal viewpoints

a. The Calvinistic view –“t.u.l.i.p.”

Total Depravity. Because of the Fall, man is spiritually dead, and every aspect of his being is tainted from the effects of sin. Man’s will is in bondage to his sinful nature so regeneration by the Holy Spirit is required to produce faith, which is a gift of God to His elect. (Rom 3:9-23;7:18; 8:5-8; 9:16)

Unconditional Election. Before the foundation of the world, God chose some from fallen humanity to be brought to salvation. This choice was based upon His sovereign grace, not on foreseen faith or works in man. God’s choice of the sinner is the ultimate cause of salvation. (Eph 1:3-2:8,9; Phil 2:13; Titus 3:5)

Limited Atonement (Particular Redemption). Christ’s death on the cross was intended to pay for the sins of the elect only and procure their redemption. The gift of faith is given to those for whom Christ died.

Irresistible Grace (Efficacious Calling). In addition to the outward invitation to salvation, the Holy Spirit extends a special inward call to the elect which inevitably brings them to salvation. Unlike the outward call, which is often resisted, the effectual calling by the Holy Spirit cannot be rejected; the elect sinner is graciously caused to cooperate with God’s plan of redemption through repentance and faith. (John 6:44; Rom 9:16; Acts 13:48)

Perseverance of the Saints. All who are elect, called, and regenerated by the Holy Spirit are eternally saved. They are kept by the power of God and persevere to the end. (John 10:28,29; Col 1:21-23).

b. The Arminian view

Free Will (Human Ability). Man was created in the image of God which included freedom of moral choice. Although the Fall separated man from God’s Spirit, he still has some spiritual capacities. Through common grace, the sinner can chose to cooperate with God’s Spirit and come to faith, or reject His convicting work and remain under condemnation. (Matt 11: 28,29; John 1:12;3:18,36)

Conditional Election. God’s choice of the elect was based upon His foreknowledge of their positive response to the gospel. Faith is not a gift of God for salvation, but a fulfillment of man’s responsibility to believe. The sinner’s choice of Christ, and not God’s choice of the sinner is the ultimate cause of salvation. (1 Pet 1:2; Rom 10:9,10; Rev 22:17)

Universal Redemption (General Atonement). Christ died to pay for the sins of the whole world. God’s love for the world includes a genuine provision for and desire for the salvation of all who believe in Christ. The application of this atonement depends upon man’s decision to receive Christ as personal Lord and Savior. (1 John 2:1,2 3:16,17; 2 Cor 5:14,15; 1 Tim 4:10; Titus 2:11; Heb 2:9)

Resistible Grace. The Holy Spirit convicts the world of sin, righteousness, and judgment, but His witness if often resisted.. Along with the external call of the gospel message, there is a spiritual illumination through the testimonies of creation and conscience. The Holy Spirit does not overrule the free will of man in accomplishing redemption. (Heb 10:29; Rom 1:18;2:15; John 5:40;14:5-11)

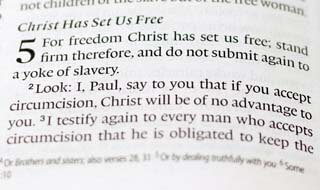

Conditional Perseverance. The born-again Christian may lose his salvation if he do not personally continue in faith and discipleship. (Gal 5:4; 1 Cor 15:2; Heb 6:1-6; 2 Pet 2:20-22) [Not all Arminians affirm this point.]

2. The need for balance.

a. Biblical theologians differ on the interpretation of these issues, and differing viewpoints need not be a cause for division in Christian fellowship.

b. The definitions, distinctions, and contrasts of these truths emphasize two basic biblical principles: the sovereignty of God (Isaiah 40) and the responsibility of man (Exodus 20). The polarization of the viewpoints seems to make God’s sovereignty and man’s free will contradict each other. Yet there is an element of truth contained in each of the five points of the Calvinistic and Arminian perspectives.

c. Because God is infinite, it is not necessary for man to fully comprehend all spiritual truths God has revealed. As time-bound and intellectually finite, man should not be surprised that God’s ways are sometimes beyond his full comprehension (Isaiah 55:8,9; Rom 11:33-36).

3. The challenge of balancing these principles

a. Illustrations of balance

Two eye’s vision blended by the brain

Two railroad tracks meeting at the horizon

Walking through a gate (Rev 22:17; Eph 1:4)

b. Examples of balance in God’s Word

The inspiration of Scripture: God’s Spirit and human authorship (2 Pet 1:20,21)

The person of Christ: fully God and fully man (John 1:1,14)

The ministry of Christ: God’s sovereignty (John 6:44;15:16;6:37-39;17:2,3); Human responsibility (Luke 19:41-44; Matt 28:19,20)

The ministry of Paul: God’s sovereignty (Rom 9,11); Human responsibility (Rom 10; 1 Cor 9:19-23;10:33; 1 Tim 4:10)

The ministry of Peter: God’s sovereignty (1 Pet 2:7-10); Human responsibility (Acts 11:14; 2 Pet 3:9)

The twofold cause of Christ’s crucifixion

“Him, being delivered by the determined purpose and foreknowledge of God , you have taken by lawless hands, have crucified, and put to death” (Acts 2:23).

“For truly against Your holy Servant Jesus, whom You anointed, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, with the Gentiles and the people of Israel, were gathered together to do whatever Your hand and Your purpose determined before to be done ” (Acts 4:27,28).

c. Need for careful interpretation of complex Scriptures

Malachi 1:2; Rom 9:13- Did God hate Esau prior to his birth?

Answer: no! God’s loves everyone (John 3:16). Malachi’s prophecy was written more than a millennium after God’s declaration (Gen 25:23) that “the elder (Esau) shall serve the younger (Jacob).” These centuries recorded the godless ways of Esau’s posterity which God rejected (“hated”).

Rom 9:14-18- Who hardened Pharaoh’s heart?

Answer: Pharaoh first hardened his own heart (Ex. 3:19; 7:14,22; 8:15; 9:34), then God judicially hardened his heart (predicted-Ex. 4:21, accomplished- Ex 9:12; 10:20,27).

Rom 9:22- Who causes people to be “vessels of wrath”?

Answer: The Greek middle voice of the verb “prepared” implies the personal responsibility of those who reject salvation, forfeit God’s grace, and thus face His wrath and their own “destruction.” Notice the contrast made to God’s love. (He endured them with “much longsuffering.”)

Since these three examples are all found in the same passage in Romans, it would be helpful to grasp the context and interpretive principles for this watershed chapter. J. Sidlow Baxter’s Explore the Book gives some important insights on Romans chapter 9:

Would it be an exaggeration to say that these three chapters have been almost if not quite the most problematical passage in all the Scriptures? They grapple with the titanic and awesome reality of an absolutely sovereign Divine will operating throughout the sin-cursed history of humanity. To my own mind, Romans ix. 18 has been the most disturbing verse in the Bible. Linked with its context, it easily seems to suggest that what we call the sovereignty of God is an unspeakably awful Divine despotism.

What are we to say about it? It is wrong to evade it. It is wrong to soften down (supposedly) the meaning of the words which Paul uses. It is wrong to force an artificial “explanation” which does not really explain at all. It is equally wrong, also (as we shall soon see), to infer, with a sort of gloating hyper-calvinism, more than is actually said. The apostle has now completed his main argument (i.-viii.),showing how the Gospel saves the individual human sinner. Glorious though this Gospel is, however, he simply cannot leave off there and affect blindness to the acute problem which it raises in relation to the nation Israel. If Gentiles are now accepted, justified, given sonship and promise, on equal footing with the Jews, what about Israel’s special covenant relationship with God? Does not this new “Gospel” imply that God has now “castaway His people which He foreknew” (xi. 2)?

If the new “Gospel” does mean that, are not God’s dealings with Israel the most hypocritical enigma and irony of history? Were not the covenant people the repository of most wonderful Messianic promises? Were not the godly among them right in anticipating Messiah’s coming as that which would end the sufferings of their people, when the scattered tribes should be regathered as one purified Israel, and the nation, so long ruled by the Gentiles, should at last be exalted over them? Yet now that Messiah had come, instead of consummation for Israel there was the most reactionary of all paradoxes–those to whom the covenant promises were given were apparently shut out, and all the long-looked-for benefits were going to Gentile outsiders!

Well, that is the background problem of Romans ix.-xi., and it is vital to realise it in considering any of the foreground statements separately. But besides this, if we are going to interpret truly any of these Pauline statements on the Divine sovereignty,we must keep to the point and the scope of the passage. As to the former, Paul’s purpose is to show that (a) the present by-passing of Israel nationally is not inconsistent with the Divine promises(see ix. 6-13); (b) because Israel’s present sin and blindness nationally is overruled in blessing to both Jews and Gentiles as indlividuals (see ix. 23-xi. 25); (c) and because “all Israel shall yet be saved” at a postponed climax, inasmuch as “the gifts and calling of God are irreversible” (see xi. 26-36). As to the scope of the passage, it will by now have become obvious that it is all about God’s dealings with men and nations historically and dispensationally, and is not about individual salvation and destiny beyond the grave [emphasis added]. Now that is the absolutely vital fact to remember in reading the problem-verses of these chapters, especially the paragraph ix. 14-22.

John Calvin is wrong when he reads into these verses election either to salvation or to damnation in the eternal sense. That is not their scope. They belong only to a Divine economy of history. Paul opens the paragraph by asking: “Is there then unrighteousness with God?”–and the rest of the paragraph is meant to show that the answer is “No” ; but if these verses referred to eternal life and death, there would be unrighteousness with God; and that which is implanted deepest in our moral nature by God Himself would protest that even God has no honourable right to create human beings whose destiny is a predetermined damnation.

No, this passage does not comprehend the eternal aspects of human destiny: Paul has already dealt with those in chapters i-viii. It is concerned (let us emphasise it again) with the historical and dispensational. Once that is seen, there is no need to “soften down” its terms or to “explain away” one syllable of it. Even the awesome words to Pharaoh (verse 17) can be faced in their full force–“Even for this same purpose have I raised thee up, that I might show My power in thee, and that My name might be declared throughout all the earth.” The words “raised thee up” do not mean that God had raised him up from birth for this purpose: they refer to his elevation to the highest throne on earth. Nay, as they occur in Exodus ix. 16, they scarce mean even that, but only that God had kept Pharaoh from dying in the preceding plague, so as to be made the more fully an object lesson to all men.

Moreover, when Paul (still alluding to Pharaoh) says, “And whom He [God] will. He hardeneth” (verse 18), we need not try to soften the word. God did not override Pharaoh’s own will. The hardening was a reciprocal process. Eighteen times we are told that Pharaoh’s heart was “hardened” in refusal. In about half of these the hardening is attributed to Pharaoh himself; in the others, to God. But the whole contest between God and Pharaoh must be interpreted by what God said to Moses before ever the contest started: “The king of Egypt will not…” (Exod. iii. 19). The will was already set. The heart was already hard. God overruled Pharaoh’s will, but did not override it. The hardening process developed inasmuch as the plagues forced Pharaoh to an issue which crystallised his sin.

Thus Pharaoh was made an object-lesson to all the earth(Rom. ix. 17). But Pharaoh’s eternal destiny is not the thing in question; and moreover in thus making an example of this “vessel of wrath” who was “fit for [such] destruction” (verse 22), God was working out a vast purpose which was not only righteous, but overrulingly gracious towards many millions of “vessels of mercy which He had afore prepared unto glory,” as we learn in verse 23!

It is always important to distinguish between Divine foreknowledge and Divine predestination. God foreknows everything that every man will do; but He does not predetermine everything that every man does. Nay, that would make God the author of sin! God foreknew that Esau would despise his birthright; that Pharaoh would be wicked; that Moses would sin in anger at Meribah; that the Israelites would rebel at Kadesh-Barnea; that Judas would betray our Lord; that the Jews would crucify their Messiah: but not one of these things did God predetermine. To say that He did would involve Him in the libellous contradiction of predetermining men to commit what He Himself declared to be sin. God did not predetermine these sinful acts of men; but He did foreknow them, and anticipate them, and overrule them to the fulfilling of His further purposes.

We mention this because it involves Esau, Pharaoh, and Moses, all of whom Paul cites in Romans ix. Let us say two things emphatically of Paraoh in particular: (i) God did not create him to be a wicked man; (2) God did not create him to be a damned soul. And, with mental relief, let us further say that God could never create any man either to be wicked or to be eternally damned. “Is there unrighteousness with God? God forbid!” In Romans ix. we simply must not read an after-death significance into what is solely historical. Moses, because of his sin at Meribah, was denied entrance into the promised land; but would we argue that this punishment extended in anyway to the salvation of his soul beyond the grave? Thousands upon thousands of Israelites died in the wilderness because of that grievous sin at Kadesh-Barnea; but were they all lost souls beyond the grave? Look up some of the generous offerings and acts of devotion mentioned earlier in connection with some of them! – Sidlow Baxter, Explore the Book, Vol. 6 Zondervan: 1960. pp. 86-90 .

Eph 1:11; James 1:13- Is God the author of sin?

Answer: Although God “works all things after the counsel of His will,” He is not the author of sin. Satan’s rebellion was his own sinful choice, yet a mysterious part of God’s eternal plan.

Human free will was a necessary attribute of man as made in the image of God. (Man is a moral and spiritual being, unlike the animals -Gen 1:26) Adam and Eve’s original sin was their own “free” choice, yet mysteriously included and overruled in God’s eternal counsel. The loving relationship between God and His redeemed would not be coerced. Love is the mutual choice of those who share love.

4. Correctives

Balancing counsel for the Calvinist:

“Do I have any pleasure at all that the wicked should die?” says the Lord GOD, “and not that he should turn from his ways and live?”(Ezekiel 18:23).

“So you, son of man: I have made you a watchman for the house of Israel; therefore you shall hear a word from My mouth and warn them for Me. When I say to the wicked, ‘O wicked man, you shall surely die!’ and you do not speak to warn the wicked from his way, that wicked man shall die in his iniquity; but his blood I will require at your hand. Nevertheless if you warn the wicked to turn from his way, and he does not turn from his way, he shall die in his iniquity; but you have delivered your soul. Therefore you, O son of man, say to the house of Israel: ‘Thus you say, “If our transgressions and our sins lie upon us, and we pine away in them, how can we then live?”‘Say to them: ‘As I live,’ says the Lord GOD, ‘I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live. Turn, turn from your evil ways! For why should you die, O house of Israel?'”(Ezekiel 33:7-11).

“For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Timothy 2:3,4).

Balancing counsel for the Arminian:

“Simon has declared how God at the first visited the Gentiles to take out of them a people for His name” (Acts 15:14).

“For whom He foreknew, He also predestined to be conformed to the image of His Son, that He might be the firstborn among many brethren. Moreover whom He predestined, these He also called; whom He called, these He also justified; and whom He justified, these He also glorified” (Romans 8:29,30).

“Being confident of this very thing, that He who has begun a good work in you will complete it until the day of Jesus Christ” (Philippians 1:6).

5. Examples in C.S. Lewis

These two principles of divine sovereignty and human responsibility are illustrated in how people become children of God. Consider these two excerpts from the testimony of British scholar and devout Christian, C.S. Lewis. Quotes are from Surprised by Joy.

a. The principle of human responsibility illustrated in C.S. Lewis:

“The odd thing was that before God closed in on me, I was in fact offered what now appears a moment of wholly free choice. In a sense. I was going up Headington Hill on the top of a bus. Without words and (I think) almost without images, a fact about myself was somehow presented to me. I became aware that I was holding something at bay, or shutting something out. Or, if you like, that I was wearing some stiff clothing, like corsets, or even a suit of armour, as if I were a lobster. I felt myself being, there and then, given a free choice. I could open the door or keep it shut; I could unbuckle the armour or keep it on. Neither choice was presented as a duty; no threat or promise was attached to either, though I knew that to open the door or to take off the corslet meant the incalculable. The choice appeared to be momentous but it was also strangely unemotional. I was moved by no desires or fears. In a sense I was not moved by anything. I chose to open, to unbuckle, to loosen the rein. I say, “I chose,” yet it did not really seem possible to do the opposite. On the other hand, I was aware of no motives. You could argue that I was not a free agent, but I am more inclined to think that this came nearer to being a perfectly free act than most that I have ever done. Necessity may not be the opposite of freedom, and perhaps a man is most free when, instead of producing motives, he could only say, “I am what I do.” Then came the repercussion on the imaginative level. I felt as if I were a man of snow at long last beginning to melt. The melting was starting in my back — drip-drip and presently trickle-trickle. I rather disliked the feeling.”

b. The principle of divine sovereignty illustrated in C.S. Lewis:

“Total surrender, the absolute leap in the dark, were demanded. The reality with which no treaty can be made was upon me. The demand was not even ‘All or nothing.’ I think that stage had been passed, on the bus-top when I unbuckled my armour and the snow-man started to melt. Now, the demand was simply ‘All.’ You must picture me alone in that room at Magdalen, night after night, feeling, whenever my mind lifted even for a second from my work, the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. In the Trinity Term of 1919 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England. I did not then see what is now the most shining and obvious thing; the Divine humility which will accept a convert even on such terms. The Prodigal Son at least walked home on his own feet. But who can duly adore that Love which will open the high gates to a prodigal who is brought in kicking, struggling, resentful, and darting his eyes in every direction for a chance of escape? The words “compelle intrare”, compel them to come in, have been so abused by wicked men that we shudder at them; but properly understood, they plumb the depth of the Divine mercy. The hardness of God is kinder than the softness of men, and His compulsion is our liberation.”

Conclusion

Recalling the Reformation, we celebrate the recovery of the Bible and justification, but let’s allow God’s Word to continue to be the final arbiter of doctrine and practice, even when that requires standing against popular views. Always reforming…would include:

*sanctification by faith,

*the priesthood of all believers,

*the role of small groups (as the Lord Jesus modeled),

*believer’s baptism,

*and commitment to world missions by the power of the Holy Spirit.

May the Lord give us a sense of Christ-like balance in advancing His kingdom, that we may honor God’s sovereignty while fulfilling our responsibilities.

Copyright 2000 by John Woodward. Permission is granted to reprint for noncommercial use when credit is given to the author and GraceNotebook.com

For further reading, see:

gracenotebook.com/foreknowledge-predestination-and-election-part-1-of-2/ Mark Cambron

gracenotebook.com/foreknowledge-predestination-and-election-part-2-of-2/ Mark Cambron

Beyond Calvinism & Arminianism: An Inductive, Mediate Theology of Salvation, by C. Gordon Olson

Chosen But Free: A Balanced View of God’s Sovereignty and Free Will, by Norman L. Geisler

The Faith of God’s Elect: A Comparison Between the Election of Scripture and the Election of Theology, by John F. Parkinson

What Love is This?, by Dave Hunt